With the end of each presidency in the 21st century, historian Julian Zelizer has assembled a cast of colleagues to evaluate the outgoing administration. The first two installments in this series focused on George W. Bush (2010) and Barack Obama (2018) and featured essays by Nelson Lichtenstein, Mary Dudziak, Kevin Kruse, and other major names in the historical profession.

In the new volume The Presidency of Donald J. Trump: A First Historical Assessment, Zelizer and more than a dozen other historians offer their insights on the Trump administration. The project captured the former president’s attention last year, after he had begrudgingly left office. Trump requested—and secured—a Zoom meeting with Zelizer and the other authors attached to the project, during which he hoped to “tighten up some of the research” they were conducting. Fortunately, Trump’s attempt at meddling failed. Although the essays included here are fair and thoughtful, they also don’t pull any punches.

They do, however, reveal some of the challenges inherent in the project of what historians call “recent history”—the study of events and processes that have unfolded over the past several years or decades. “Recent history” differs from journalism in its emphasis on historical analysis and context. Because its practitioners want to determine how and why contemporary phenomena came to be, they home in on the linkages, and discontinuities, between the distant past, the more recent past, and the present. And, as historians Claire Potter and Renee Romano explain in a book on the topic, recent history “talks back,” as circumstances change and living subjects, like Trump, vie to control the dominant narrative. Since these scholars are analyzing ongoing developments—and doing it in the rigid format of a published book, no less—some of their assessments are already outdated or, at the very least, incomplete.

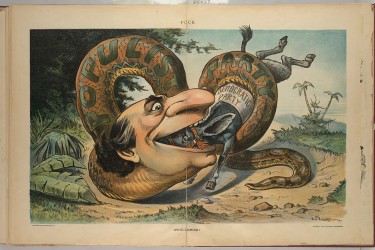

This particular “recent history” is even more difficult, given historians’ visceral (yet varied) responses to Trump’s candidacy and presidency. His emergence in 2015 and 2016 raised major philosophical, definitional, and strategic questions within the historical profession. How, and to what extent, many historians wondered, should we “resist” Trumpism? Some historians—including several featured in Zelizer’s new volume—wrote, circulated, and signed online petitions highlighting the existential threat that Trump ostensibly posed to U.S. democracy. Now-familiar names like Heather Cox Richardson, Joanne Freeman, and Kruse became influential public intellectuals during Trump’s term, sharing their historical wisdom with hundreds of thousands of online #Resisters, many of whom believed that Trump and the contemporary GOP were subverting otherwise noble American institutions and traditions. Other academics, coming from the left, criticized historians like Timothy Snyder for their attempts to characterize Trump as a fascist and to frame his popularity as an exceptional phenomenon, rather than a logical outgrowth of racism, capitalism, xenophobia, sexism, and other malign forces that have long defined the American experience.