The stories that a country tells itself are just as critical to its functioning as its army, its laws, its borders, and its flag. Where did the country emerge from, and where might it be heading?

Such questions of national mythology are especially fraught in the United States, still relatively young in the world, big, rich, powerful, multiethnic, and operating on a set of profoundly contradictory ideas. That it might be possible to make sense of American political division by naming those myths and interpreting the news of the day through their filter is the guiding ambition of Richard Slotkin’s exciting and detailed new decoder ring of a book, A Great Disorder: National Myth and the Battle for America.

The title is an homage to the Wallace Stevens poem “Connoisseur of Chaos,” which declares that “a great disorder is an order”—not just as a metaphysical statement but also as a tidy description of the contested historiography of the United States. Can we look into our past to find the white, Christian, hierarchical, free-market society of red America’s imagining? Or do we see the imperfect but ever-striving egalitarian and multiethnic vision of blue America? Both sides have told selective stories, which are neither completely true nor exactly false.

“Each has a different understanding of who counts as American,” writes Slotkin, “a different reading of American history, and a different vision of what our future ought to be.” His goal in the first part of the book is to describe and unpack “America’s foundational myths to expose the deep structures of thought and belief that underlie today’s culture wars.” In the second part of the book, Slotkin directly applies those collective stories to make sense of the tumultuous last eight years.

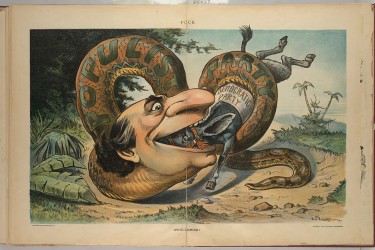

It is difficult to imagine a more qualified author for this freighted task. Slotkin has made a career out of dissecting grand national myths. He is an emeritus endowed chair of English and American studies at Wesleyan University and the author of a trilogy of books on what he calls the “Myth of the Frontier.” Two of them were National Book Award finalists, and his argument in Regeneration Through Violence: The Mythology of the American Frontier, 1600–1860 (1973)—that European settlers learned the ways of Indigenous Americans only to convert them into tools of repression and genocide—has influenced the historiography of colonial America enormously.