Imagine, if you will, that millions of hard-working Americans finally reached their boiling point. Roiled by an unsettling pattern of economic booms and busts; powerless before a haughty coastal elite that in recent decades had effectively arrogated the nation’s banks, means of production and distribution, and even its information highway; burdened by the toll that open borders and free trade imposed on their communities; incensed by rising economic inequality and the concentration of political power—what if these Americans registered their disgust by forging a new political movement with a distinctly backward-looking, even revanchist, outlook? What if they rose up as one and tried to make America great again?

Would you regard such a movement as worthy of support and nurture—as keeping with the democratic tradition of Thomas Jefferson and Andrew Jackson? Or would you mainly dread the ugly tone it would inevitably assume—its fear of the immigrant and the Jew, its frequent lapse into white supremacy, its slipshod grasp of political economy and its potentially destabilizing effect on longstanding institutions and norms?

To clarify: This scenario has nothing whatsoever to do with Donald Trump and the modern Republican Party. Rather, it is a question that consumed social and political historians for the better part of a century. They clashed sharply in assessing the essential character of the Populist movement of the late 1800s—a political and economic uprising that briefly drew under one tent a ragtag coalition of Southern and Western farmers (both black and white), urban workers, and utopian newspapermen and polemicists.

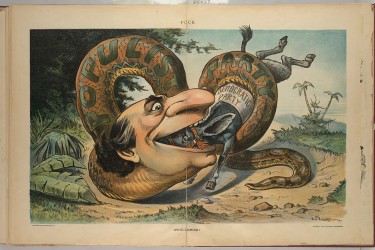

That debate pitted “progressive” historians of the early 20th century and their latter-day successors who viewed Populism as a fundamentally constructive political movement, against Richard Hofstadter, one of the most influential American historians then or since. Writing in 1955, Hofstadter theorized that the Populists were cranks—backward-looking losers who blamed their misfortune on a raft of conspiracy theories.

Hofstadter lost that debate: Historians generally view Populism as a grass-roots movement that fought against steep odds to correct many of the economic injustices associated with the Gilded Age. They write off the movement’s ornerier tendencies by pointing out—with some justification—that Populism was a product of its time, and inasmuch as its supporters sometimes expressed exaggerated fear of “the secret plot and the conspiratorial meeting,” so did many Americans who did not share their politics.

But does that point of view hold up after 2016? The populist demons Trump has unleashed—revanchist in outlook, conspiratorial in the extreme, given to frequent expressions of white nationalism and antisemitism—bear uncanny resemblance to the Populist movement that Hofstadter described as bearing a fascination with “militancy and nationalism … apocalyptic forebodings … hatred of big businessmen, bankers, and trusts … fears of immigrants … even [the] occasional toying with anti-Semitic rhetoric.”

A year into Trump’s presidency, the time is right to ask whether Hofstadter might have been right after all about Populism, and what that possibly tells us about the broader heritage of such movements across the ages.

***