This leaves history in an odd spot—more publicly rassled with, yet far from receptive to taming on the ground. History is a bit like prosperity, another popular specter for politicians. It can be adduced and celebrated and promised without ever needing to be produced, as an actual thing. The actual things being changed and argued over tend to be the names of recent political figures—Hillary Clinton and George Soros, for instance—and then the constantly roiling cloud that is the American Civil War. Slavery and Federalism go in, and then someone takes them out. It’s small, grimy work that is likely overwhelmed by the mist of online keywords. Removing any Clinton from a history book is, almost stem to stern, just a smaller and slower kind of filibuster.

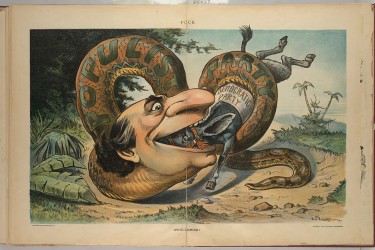

The Gingriches tend toward a kind of historical editing that largely wants the least context possible, with the fewest obscure names. The other side, loosely referred to as the left, creates trouble by pointing out that enslaved people were enslaved. But the two sides, over time, have hardened into two groups whose combination seems unlikely. One cohort seems to believe in the process of inquiry and modification of proposals subsequent to ongoing discovery and argument. You could call these people fans of dialectical critique and not be entirely wrong. The other cohort simply wants A Story, an untouched delusion that is chosen and then simply reinstalled as time goes by. Whatever conservative values may have meant before, they have metastasized into some advanced fever of the Lee Atwater 1980s, with patriotism reiterated daily as a loose blend of gun mayhem, wide-spray racism, and deep, passionate aversion to the idea that there is anything like a system operating anywhere in America, or the world. Any political persuasion can become a fan of myth, despite a general tendency for the left to reject delusion, it’s true. But nobody can choose myth and inquiry both—it’s as zero as zero sum gets.