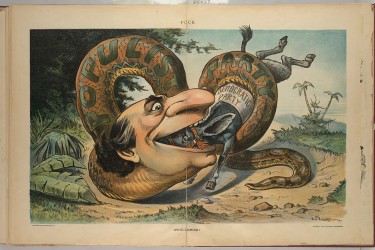

“Patriotic education” — a merger of Stephen Miller’s fascism with Mike Pence’s fundamentalism — is both old and new. It is a return to the “great man” vision of history long taught (and still often taught) to our children, not to mention the biblical education that dominated American schools until the 1930s. But what once was an unexamined given of a white supremacist system is now a weapon, mobilized in explicit opposition to examination of slavery’s centrality in U.S. history. As Jean Guerrero writes in Hatemonger, her political biography of Trump commissar Stephen Miller, Trump’s intellectuals recognize the larger restructuring of knowledge necessary to the triumph of personality as power. For Miller and the cynics and believers who provide Trump with the targets to which he applies his invective, Trump isn’t everyman, he’s uberman. His “victories” — whether in fact or in declaration — are presented as “your” victories. You win when he wins, because whiteness wins. “That which God has given us,” as Trump proclaimed on July Fourth at Mount Rushmore. That speech, in which Trump paid tribute to the genocidal doctrine of Manifest Destiny, was widely seen as his historical turn, the moment in which his speechwriters began to retrofit “Make America Great Again” with a right-wing revisionist history that casts Trump’s ascendency as inevitable.

But Trump has long subscribed to a typically Trumpian take on what Nietzsche called “the uses and abuses of history.” Overlooked in 2016 was an early meeting with conservative evangelical leaders at which, according to Christian bestseller God’s Chaos Candidate by Trump evangelical adviser Lance Wallnau, Trump proposed his merger with the Christian right in “historical” terms: “We had such a long period of Christian consensus in our culture that we kind of got… spoiled. Is that the right word?” he asked. “We’ve had it easy as Christians for a long time in America. That’s been changing.” In public, he spoke of “our Christian heritage,” a phrase so seemingly absurd coming from his mouth that critics failed to take stock of the historical project embedded within it. Privately, he told this gathering of evangelical leaders that “Christians” — he’d picked up on their belief in themselves as the only ones worthy of the name — had gotten “soft,” that it was time to be hard, to concede nothing, to brand it all — past as well as future.

“Trump spoke their language and told their stories,” writes Harvard Divinity School scholar Lauren R. Kerby in her new book Saving History, a study of the booming Christian nationalist alt-history tourism industry. That is, he distilled Christian nationalism’s historical jeremiad of a fallen nation into a four-word formula for its certain restoration: “Make America Great Again.” At Mount Rushmore, and again at the National Archives on Thursday, he spoke of history not as the ongoing study of an only partly knowable past but as an “unstoppable” force. There is no debate to be had, no consideration, for instance, of the 1619 Project as part of a larger conversation — only variables to be plugged into a fundamentalist equation of history that always equals Trump.