Donald Trump’s rise to power triggered a great deal of soul searching, not least of all among historians, almost of all of whom failed to see his election as plausible, let alone likely. In an essay in the New York Times Magazine, the popular political historian Rick Perlstein offered readers a mea culpa on behalf of an entire field. “The professional guardians of America’s past,” he confessed, “had a made a mistake.” Historians’ accounts of American politics were far too constricted. If Trump was “the latest chapter of conservatism’s story,” he worried, “might historians have been telling that story wrong?”? His answer was an emphatic yes.

Perlstein called for an expanded conception of who and what counts as “conservative.” The Republican coalition, he argued, should be stretched to include the “sheer bloodcurdling hysteria” of those within the white nationalist, alt-right. Some scholars who have begun wrestling with the Trump phenomenon agree, explaining that historians too often discount the role of fringe political movements or ideologies within mainstream coalitions. The tragedy in Charlottesville and the renewed political salience of Confederate memorials brings even greater urgency to this project.

To be sure, students of American politics must cast a wider net. But perhaps the most important insights to be gained from focusing on a small but extreme shard of the American electorate may be in what they can teach us about the real source of Trump’s power: the silent majority of Republican voters who were willing to ignore or quietly accept Trump’s venal nativism. If anything, the alt-right’s emergence will help contextualize the far more numerous and “respectable” conservatives, clarifying what exactly these voters are willing to tolerate or accept in order to maintain political power.

At the same time, however, there is reason to be skeptical about the value of folding the alt-right into our red- and blue-hued conceptions of mainstream politics. Doing so may only further flatten our political conversation, smoothing important gradations of outlooks, experiences, and contexts back into the numbing and maddeningly amorphous categories of “left” and “right,” “liberalism” and “conservatism,” and “blue” and "red.” Indeed, one could argue that the overreliance by media and scholars on these categories blinded many of us to the plausibility of Trump’s rise in the first place.

For too long, academics and pundits have defined “the political” in American life with recourse to partisanship and the two dominant political ideologies. Other political forces, factors, and experiences have either been ignored or squeezed into these categories, normalizing or whitewashing extreme positions in the process. As a result, our political conversation has been at once woefully incomplete and totalizing.

And so we should cast a wider net. But we must be more precise about the kinds of political forces we catch – liberalism and conservatism alone no longer explain the political forces at work in American life, if they ever did. If we remove our red- and blue-tinted lenses, we might discover that many historical explanations for 2016’s head-spinning political turn were in front of us all along.

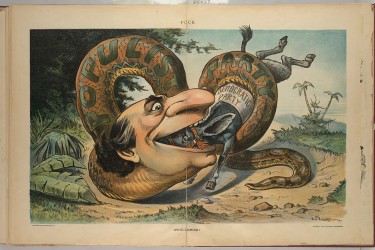

Trump’s ascendancy is not the first time a presidential election has touched off a crisis of confidence among students of American politics. Nearly four decades ago, Ronald Reagan’s election launched scholars and journalists on quests to answer a suddenly urgent question: Why didn’t they see Reagan coming? At the time, many of the most influential scholars were writing from what they understood to be a more inclusive perspective. Whereas an earlier generation of “consensus” historians had struck a self-consciously centrist posture – writing “Great Men” histories of high politics somewhere between the poles of communism on the far left and John Birch Society “paranoia” on the fringe right – these younger scholars were interested in a diverse array of regular people, both as subjects of historical inquiry and as agents of historical change. By the late 1980s, however, shocked at the contemporary political turn, many feared they lacked historical explanations for what appeared to be the end of liberalism.

In 1989, an answer came in the form an influential volume titled The Rise and Fall of the New Deal Order. The book described an era of liberal dominance inaugurated by Franklin Roosevelt’s election in 1932 and ultimately eclipsed by Reagan in 1980. These scholars described a “dominant order of ideas, public policies and political alliances” as well as the “missed opportunities, unintended consequences, and dangerous but inescapable compromises” that led to its collapse. The essential constituency in much of the New Deal order literature was the white, male working class. In the wake of deindustrialization, the declining fortunes of labor, and mounting racial tensions and suspicion about wasteful government spending, many members of the white working class had become so-called Reagan Democrats.

This moniker, the Reagan Democrats, implied that voters had momentarily misplaced their political allegiances. But by 1994, the historian Alan Brinkley urged scholars to take “conservatism seriously” as a coherent political force. Indeed, with Republicans’ newfound control of Congress in the mid-nineties, it was clear that something much more durable had emerged. Over the ensuing decade, a new generation of scholars balanced “the New Deal order” literature with its opposite: the rise of modern conservatism. They located important studies in Sunbelt suburbs, evangelical church halls, and among a handful of economists and publishers who fused staunch anti-communism, anti-statism, and free market values. These scholars discovered activists within American conservatism to be a “thoroughly modern group of men and women.” Rather than write disparaging histories of the paranoid reactionaries imagined by midcentury consensus scholars like Richard Hofstadter, a new generation of political historians wrote conservatism into the American political tradition.

But these analytical projects – the New Deal order and the rise of modern conservatism – proved wholly insufficient for explaining Trump’s capture of the Republican Party, let alone the White House. And so a number of thinkers have begun to weigh in. Writing in The Atlantic, the conservative journalist and outspoken Trump critic David Frum rightly notes that Perlstein’s wider partisan net approach risks abdicating the “study of continuity and discontinuity” which “is literally the historian’s job.” In other words, simply projecting today’s alt-right onto the past may tell us little about important changes that enabled Trump to capture the Republican Party, and even less about those groups’ political roles in the past. Less helpfully, Frum explains Trump’s rise by referencing a constellation of ahistorical forces – egalitarianism, cultural chauvinism, and cosmopolitanism – that somehow gelled in ways that enabled Trump to “dupe” the American electorate. While he invokes David Hume and Jean-Jacques Rousseau to explain Trump’s election, Frum is mum on what specifically made the electorate susceptible to being duped last year.

More helpfully, a number of scholars and analysts, some drawing explicitly on Marxian insights, explain the window of opportunity through which Trump stumbled with structural analysis. These forces include economic shifts and the changing strategies and weaknesses of the parties within the broader realities of inequality, globalization, and regional change. These approaches don’t so much reject Perlstein’s call for a wider net as explain how a range of forces can cause liberal or conservative coalitions to wax and wane over time. And yet, even political historians keenly attuned to such structural analysis failed to take seriously the possibility of a Trump presidency. (Though some did make the case for why Bernie Sanders could win.)

Other scholars, however, took a wholly different tack, arguing that Trump’s rise was an understandable (if less predictable) consequence of developments in how the academy teaches American political history. On the New York Times op-ed page, two scholars argued that it was an alleged turn away from teaching the formal structures of politics and political history – e.g., courses focused on congress, presidential administrations, and the party system – that played a key role in propagating the ignorance they felt provided Trump an opening. Their implication was that courses on the history of women, immigrants, or African Americans, for example, did not introduce students to the practices and institutions of “high” politics.

The response from historians across a staggering array of areas of inquiry was fast and understandably furious. In blog posts and on conference roundtables, scholars proclaimed the vibrancy of political history. Many held up as evidence the “Trump Syllabus,” a crowd-sourced compendium of books and sources released nearly five months prior to Trump’s election. (A second, expanded Trump Syllabus was soon added.) To be sure, many scholars included on the syllabi may never have identified professionally as political historians; they likely found little in the way of explanatory power in mainstream political history’s focus on electoral realignments or ideological and partisan categories. And to judge the syllabi’s books by their covers – the stance taken, perhaps, by proponents of high politics – much of the work might appear adjacent to the orthodox political history defended in the Times op-ed. But this work is political in the most profound sense: it is fundamentally concerned with the nature of rights, the exercise of public authority and discipline, and attuned to the deeper structures of power, culture, and identity that continue to shape our politics. Central to much of the work on the syllabi, it turns out, are Supreme Court decisions, acts of Congress, and, yes, even presidential elections and administrations.

In its themes and topics, the lists offer a rich account of the roiling political forces that brought Trump to the fore. These scholars understood that simply teaching “high” politics or the history of the political parties captured fragmentary or distorted views of how politics works. Within the narrow red-blue definition of political history, many broader political experiences and forces remained invisible – especially those that reflected unspoken points of consensus between parties or developments that did not seem immediately germane to electoral outcomes. The class and race politics of suburban homeownership, for example, produces segregated housing and unequal school districts, but colorblind myths of neighborhood choice remain sacrosanct within both parties.

As one recent analysis noted, some of Trump’s staunchest support came from suburban residents whose isolation encouraged the belief that they no longer owed anything to a broader common weal. The politics of real estate, it turns out, could be very useful for understanding the political appeal of our real estate president. Other works on the syllabi shed light on similarly overlooked but equally momentous aspects of our current politics. These include scholarship on Mexican immigrants and the history of American dependence upon and anxieties about expropriated foreign labor; cultural and historical studies of misogyny and ideas about the female body; and scholarship on the bipartisan origins of racial double standards in punitive policing, incarceration, and white Americans’ sense of exceptional innocence when it comes to the nation’s struggle with drugs and criminality.

In addition to illuminating an array of experiences ignored in traditional red-blue political debates, these histories also help explain what the mainstream of American politics – that is, predominantly white, middle class voters – have been willing to tolerate or, more troublingly, to accept in their maintenance of political power. These are precisely the kinds of historical inquiries that help explain why so many “respectable” voters nevertheless pulled the lever for Trump, perhaps even four years after voting for Obama. They help us understand why, for instance, Trump won white female voters by a strong margin despite his self-evident misogyny. Excavating these deeper patterns of race, culture, norms, and experience that cut across ideological and partisan lines better reveals the ways our political institutions and norms function – and for whom.

If we want to better understand American political history, expanding our conception of the "right" is a good place to start. But if we don't also expand our definition of "politics" itself, it won't be long until we're caught off-guard again.