What turned Meacham into the Age of Trump’s superstar historian was yoking this catastrophizing to some observation that things have been bad in America before and we have lived through them: the rise of the Klan, the Oklahoma City bombing, the downfall of Nixon. Temperament, rhetoric, decency, character—Meacham told us why these things mattered and what it would cost us to have a president who flouted them.

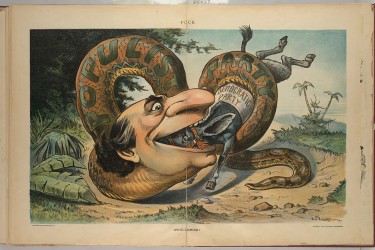

The historian pulled it all together in The Soul of America, an account of the country’s long wrestling match with intolerance. Here was the presidential-history formula for difficult moral times: Maybe America’s leaders weren’t so awesome after all, Meacham admitted. Maybe America wasn’t such a decent country, either. Yes, it had good impulses—but it also had bad ones, and sometimes the bad ones got the upper hand.

It’s a weighty concept, this soul stuff. Here is how Meacham explained it in the documentary last year: “The soul of the country is, in fact, this essence, which is not all good or all bad. You have your better angels fighting against your worst impulses. And that has a religious component, certainly. It’s also, though, a matter of historical observation.”

So: There is Good in America, Meacham tells us, and there is also Bad. These are history’s diagnostic categories. People in the past have done fine things, and they have done wicked things. As the book’s subtitle puts it, our history is an unending “battle for our better angels,” a theory the historian borrowed from a speech by Lincoln.*

It’s the dialectic of history, imagined for a new Manichaean generation: things that are Good exist in eternal conflict with things that are Bad. The imperative facing intellectuals, meanwhile, is to inform us that Good things are Good. And also: to proclaim to the world that Bad things are Bad.

Perhaps you think defining these categories would be difficult. No. Defining these categories is a snap. Bad things are the things that everyone already knows to be bad, such as slavery, bigotry, and isolationism. Good things are, similarly, the things whose goodness is well known, such as women’s suffrage and the civil-rights movement. In The Soul of America, Meacham urges us to disapprove of the Ku Klux Klan, to understand that George Wallace was not a good person, and to realize that Joe McCarthy was a dishonest individual. The quotes Meacham deploys to establish these totally standard aperçus usually turn out also to be the standard ones, the ones you would find in Familiar Quotations on High-Minded Themes, if such a book existed: a famous aphorism uttered by a beloved president; the words Edward R. Murrow used to humiliate McCarthy; the clever quotation you remember hearing in a Ken Burns documentary. These are the oft-told tales of American liberalism, told here yet again.