The intertwined effects of “free trade” and the New Democrats’ lack of concern for non-college workers in Trump’s appeal cannot be overstated. In many counties that flipped from Obama to Trump, a “high-profile plant closure or impending move had been on the front page of the local newspaper [during the campaign]: embittering reminders that the ‘Obama boom’ was passing them by,” as historian Mike Davis wrote in Jacobin in February.

The virulent racism of the KKK and the conspiratorial anti-Semitism of Ford and Coughlin, in other words, might tell us much about the modern “alt-right,” but it doesn’t tell us a lot about the marginal Trump voters who once voted for Obama and disagreed with much of Trump’s rhetoric, but voted for him anyhow. The latter decided the election, not the former.

Alongside the elision of economics in Perlstein’s analysis of Trump’s triumph, the most perplexing element of his essay is his (perhaps unintentional) acceptance of “Never Trump” conservatives’ version of history. The conservatives who opposed Trump were quick to argue that Trump shared nothing in common with conservative heroes like Buckley, Goldwater, and Reagan.

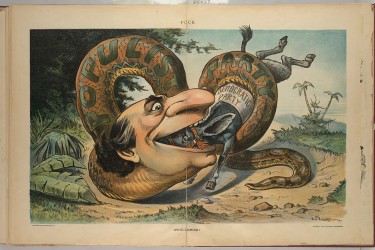

Like these conservatives, Perlstein’s essay places the likes of Buckley, Goldwater, and Reagan on the respectable side of the ledger and calls upon historians to look for the roots of Trump in “conservative history’s surrealists and intellectual embarrassments, its con artists and tribunes of white rage.” But as historian Kevin Mattson, political scientist Corey Robin, and legal scholar Ian Haney López, among many others, have shown, the history of figures like Buckley, Goldwater, and Reagan and the history of conservatism’s “surrealists and intellectual embarrassments, its con artists and tribunes of white rage” is one and the same.

Trump’s incipient fascism, polarizing racism, and loose connection to the facts don’t represent a break from the main currents of modern American conservatism; they embody it.