Now, as a large number of white evangelicals have come to define Trump’s power base—and as the president has pitched his rhetoric and campaign primarily toward shoring up that base—Trump, like so many evangelical leaders, has turned to American history.

The extent of that transformation can be seen in Trump’s RNC speech in August. Comparing Trump’s major speeches from 2016 to the present day shows just how much he has shifted toward American exceptionalism. Yet even as he embraces Reagan’s rhetoric, his re-telling of American history is—incredibly—even whiter and less multicultural than Reagan’s. Reagan at the very least talked of immigrants from all lands seeking America’s shores. He touted the United States as a place of asylum. He described John Winthrop, the first Puritan governor, as looking for freedom in the same way as a refugee in the South China Sea. No one could claim that Reagan embraced critical race theory, but his speeches now and then recognized that multiple races make up the fabric of American history.

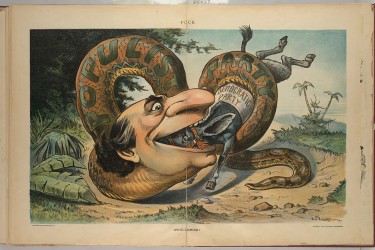

As Trump rounded out his long RNC speech, his exalted rhetoric did no such thing. “Our American ancestors,” he declared, “sailed across the perilous ocean to build a new life on a new continent.” The enslaved, we learn, are not part of this tale. After arriving, Trump continued, “our” American ancestors “picked up their Bibles, packed up their belongings, climbed into covered wagons, and set out West for the next adventure.” Native Americans, we learn, are not part of this tale. Once out west, Trump persisted, “our” heroic, Bible-wielding ancestors staked a claim “in the wild frontier,” building “beautiful homesteads on the open range.”

Again and again, Trump’s history of America includes only the deeds of white people (and only some deeds at that). A new life on a new continent. An open range. A frontier “wild” with a faceless foe. And all of it tamed, settled, and built by heroes with Bibles in hand, establishing churches across the land. The 1619 Project is not without its problems. But to counter the 1619 Project, Trump has begun telling a history of the U.S. that reveals exactly why we need it in the first place. In Trump’s telling, “our American ancestors” are largely Christian and largely white—just like his base.

What we see in Donald Trump’s recent embrace of American exceptionalism, in other words, is that evangelicals have reshaped Trump as much as Trump has reshaped them. The influence has gone both ways. In 2016, as I have noted elsewhere, the phrase “city on a hill” drove a wedge between the Reagan remnant and the tribe of Trump. In 2020, the tribe of Trump has turned him back to Reagan’s rhetoric of a Christian America embraced by his evangelical base.