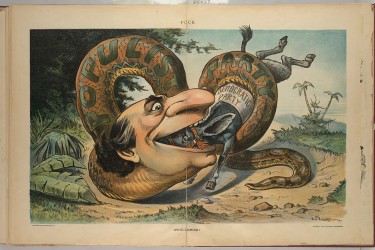

It’s unusual that the Republican Party’s most recent standard-bearer, President Donald Trump, has disavowed the very idea of “American exceptionalism.” “I don’t think it’s a very nice term,” he said. “I think you’re insulting the world.” But that doesn’t mean that Trump has chucked this dearly held principle. When most conservative politicians invoke the term “exceptionalism” they use it as shorthand for raw national chauvinism—the assertion that the United States is not just different, but better. Trump has replaced it, at least temporarily, with an angrier tag line that conveys the same sense of national power and entitlement—America First, itself a term ripped from history and freighted with dark meaning. When America is first, it owes little to everyone else. It’s a more Trumpian way of saying what other politicians often mean.

When they use the term “exceptional” to connote pure superiority, though, politicians generally betray a facile grasp of history. In its original formation, American exceptionalism was a much more complicated theory. It conveyed the idea that the United States was immune from social, political and economic forces that governed other countries—specifically, that it was invulnerable to communism and fascism, and to violent political convulsions of the sort that jolted Europe throughout the long 19th and 20th centuries. It also implied that Americans bore a providential obligation to be exemplars of virtue in a sinful world.

Exceptionalism was for many decades a hotly contested topic among historians and social scientists. Could arbitrary borders really render an entire country exempt from broader social, economic and political forces, particularly in an age when these borders became more porous to the movement of capital and labor? Or did patterns of political development in fact create unique forms of national “character”?

In more recent years, the debate cooled. While some political scientists continued to explore potential variants of American exceptionalism, most historians concluded that the idea was meaningless and the very conversation itself stale.

Then came Trump.

His election and the conditions that accompanied it—a growing rejection of science and evidentiary fact, extreme political tribalism, the rise of conservative nationalist movements around the world, a popular reaction to immigration and free trade—may offer final and conclusive proof that there is nothing at all exceptional about the United States. We are fully susceptible to the same forces, good and ill, that drive politics around the globe.

But before we sound a death knell for the idea, it would help to remember what it actually means.