Is Donald Trump a madman? Or, at least, would he like foreign leaders to think he might be just a little unstable? Such questions are being batted around in papers like the Boston Globe and the Washington Post in response to the president-elect’s foreign policy moves: his provocations toward China, his attacks on NATO and the UN, his warm overtures toward Rodrigo Duterte and Vladimir Putin.

Across the pundit-sphere, analysts are asking, is he crazy, or crazy like a fox?

In no context is the question more pertinent than Trump’s position on nuclear weapons. His comments both as candidate and president-elect show a more cavalier attitude toward their proliferation and use than any president in the past 30 years. “You want to be unpredictable,” Trump said last January on Face the Nation when asked about nuclear weapons. More recently, he tweeted that it was time for the US to start stockpiling nukes again. The comments prompted instant parallels to Richard Nixon’s “madman theory” of foreign relations: the idea that the president couldn’t be controlled — including where America’s nuclear arsenal was concerned — so foreign leaders should do everything in their power to appease him.

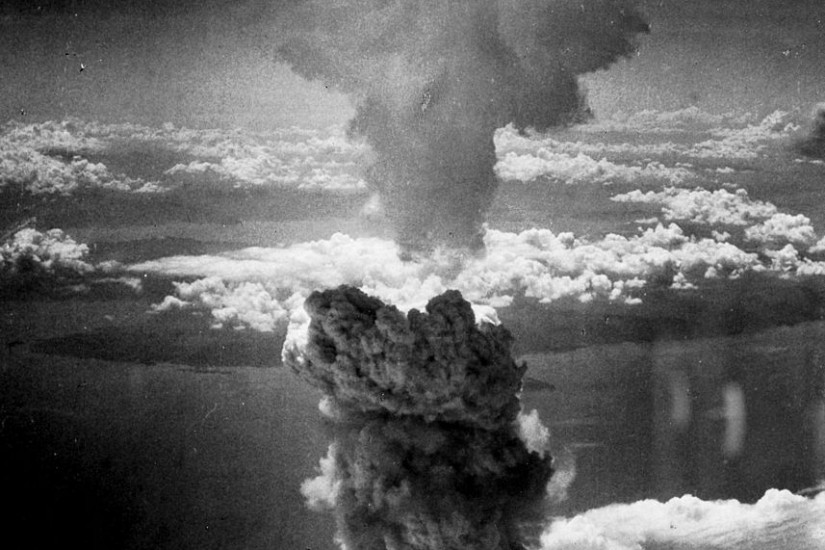

The madman question is so important here because madness has been a mainstay of nuclear culture since the atomic age flashed into being in the Jornada del Muerto desert in 1945. The bomb, carefully engineered by some of the 20th century’s most brilliant scientists, able to raze cities and civilizations, has always spanned rationality and irrationality, logic and madness.

The brightest minds created the most destructive force, and then leaders spent years working out rationales for its world-ending use. It was a madness begot by logic. But that madness doesn’t always present in the same way, which is why the history of nuclear madness has to precede our understanding of the Trump-as-madman debate.