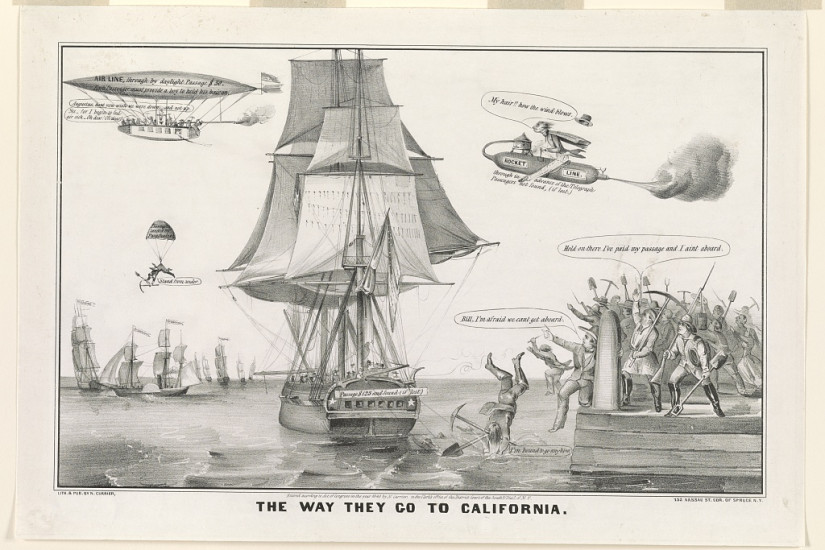

There’s little in Currier’s frolicsome scene that suggests serious violence, which is fitting, since many Americans have regarded the pursuit of prosperity and the westward “expansion” of the United States as simple processes of progress—the gradual rise of civilization on a largely empty continent. Even today leading American history textbooks offer airy chronicles of “the nation’s founding and its expansion through migration, immigration, war, and invention.”

Yet “expansion” is a euphemism for imperialism, and “migration” has often meant violent incursion. In California in 1849, some 150,000 Indigenous people—from Miwoks in the north to Chumash people in the south and hundreds of communities in between—lived alongside a limited number of Spanish missionaries. They were the survivors of the first waves of colonialism in the area, tens of thousands of Native people having died in and around Spanish mission towns after their first establishment in 1769. Worse was soon to come. Before the 1849 gold rush, many of those living outside the Spanish presidios still managed to maintain their traditional lifeways largely independent of the nonnative world. By 1870, after some 300,000 US whites had rushed into the region hoping to find gold, about 120,000 more of the original inhabitants had died, leaving just 30,000. Rather than filling a vacuum, settlers aggressively invaded, stole Native lands, and nearly annihilated Native Californians.2

However reluctant white Americans have been to confront the full history of US expansion in North America, Native people have never not known about it. In 1920 the publishers of a book by the Oneida historian Laura Cornelius Kellogg, Our Democracy and the American Indian, admitted that “for four centuries the white man has put off the day of reckoning with the American Indian.” It has now been five centuries. Though academic specialists have started to speak of “American genocide” in monographs published by university presses, popular myth has continued to promote the idea of the US as a benign nation animated by benevolent ideals.

Now, more than a century after Kellogg tried to complicate that story, we may finally be at a historical and moral turning point. Major new books written by eminent scholars for general readers about the peoples who lived in North America for millennia before the arrival of Europeans promise to reshape the history of the continent. They include Kathleen DuVal’s Native Nations: A Millennium in North America, Pekka Hämäläinen’s Indigenous Continent: The Epic Contest for North America, and Ned Blackhawk’s National Book Award–winning The Rediscovery of America: Native Peoples and the Unmaking of US History.