Editor’s Note: Over the course of 2022 and 2023, New American History Executive Director Ed Ayers is visiting places where significant history happened, and exploring what has happened to that history since. He is focusing on the decades between 1800 and 1860, filing dispatches about the stories being told at sites both famous and forgotten. This is the 24th installment in the series.

After three weeks of exploring the American West, through Oklahoma, Kansas, Nebraska, Wyoming, Colorado, and Texas, winding through stories separated by decades and hundreds of miles, Abby and I headed back home to Virginia. The trip would take us through Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, and our home state of Tennessee. We’d be ending our journey by passing through the landscape of slavery.

We found an RV park near the French Quarter in New Orleans, and parked Bertha almost directly underneath Interstate 10 and massive billboards for the state lottery. From there, we were able to set off on foot to many of the places we wanted to see in New Orleans.

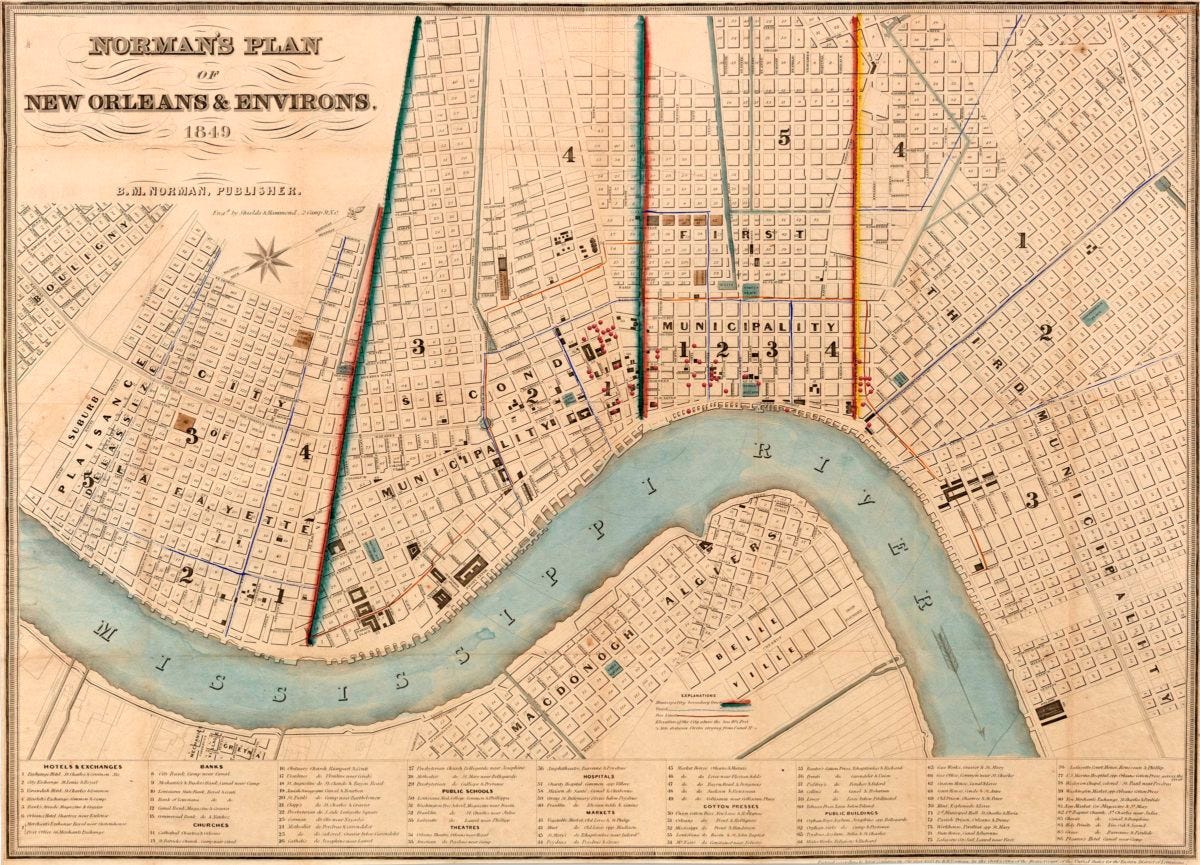

What I didn’t see as we walked through the heart of the city were many acknowledgements of enslavement. New Orleans dominated the slave trade in the Lower South, channeling hundreds of thousands of Black Americans from the Upper South through its massive docks into stores, hotels, open markets, and private homes in the city and into the burgeoning plantations of the Lower South.

In 2017, the Historic New Orleans Collection (THNOC) put together a wide-ranging exploration of that slave trade, in conjunction with several of my friends and colleagues in Richmond. It included conferences about the gathering of enslaved people for sale in Virginia, and about their sale in Louisiana. THNOC (which happened to be under renovation when we visited) displays wall posters about that work in a nearby branch site, but did not stage a full exhibit about the project.

The Historic New Orleans Collection did host a compact but multifaceted exhibit about the French Quarter. There, it presented a brief but frank acknowledgement of the role of bondage in a city. “From the first decade of the city’s settlement,” it reads, “slavery was a ubiquitous element of everyday life — affecting all facets of the local economy and culture.” It explains that the domestic slave trade with the Upper South “was the primary economic engine of pre-Civil War New Orleans — and many of the public auctions, private sales, brokers, banks, and related mechanisms of the slave system operated within the French Quarter.”

Anyone who read and reflected on this statement would likely see the festive streets of New Orleans in a new light. “Enslaved men, women, and children were sold at auction alongside dry goods, livestock, finished material goods, and any other conceivable piece of property. Slave sales often took place in startlingly visible and high-profile locations, such as within the rotunda of the St. Louis Hotel, the site of today’s Omni Royal Orleans, next door to this gallery.”

In the meantime, the ubiquity of slavery in New Orleans meant there was not one place where the story might be anchored. It was fitting and helpful, therefore, that a mobile app allows visitors to walk through New Orleans and hear about acts and places that could no longer be seen. The product of the New Orleans Tricentennial Commission of 2018, the app notes that as late as 2017, “the city of New Orleans had just one marker testifying to the history of the domestic slave trade” — a privately installed plaque in the wrong location. The Commission, under the leadership of historian Erin M. Greenwald, erected markers or plaques in six locations and launched the app. It includes first-person testimonies of people traded as property in the New Orleans Market, and is an effective use of a freely shared resource.

The history of Black people in New Orleans, of course, encompassed much more than slavery. Everyone acknowledges that the food and music of New Orleans, its major sources of identity, would not exist without the skills, traditions, and creativity of Black people.

The longer history of Black music is anchored in Congo Square, within walking distance of the entertainment district. There, a striking statue captures the joy and camaraderie people of African ancestry created for themselves as early as 1740. A sign explains that “by 1803, Congo Square had become famous for the gatherings of enslaved Africans who drummed, danced, sang and traded on Sunday afternoons. By 1819, these gatherings numbered as many as 500 to 600 people.” No visitor to antebellum New Orleans could fail to visit the scene. The performance and traditions that began there grew into Mardis Gras, jazz, and rhythm & blues.

While it would be wrong to extrapolate about the happiness of dancing and singing slaves, it is also important to acknowledge the ways people of African descent sustained themselves and their identities. Much that is distinct and vibrant in American culture is the product of Black invention and memory. Congo Square helps link us to that past.

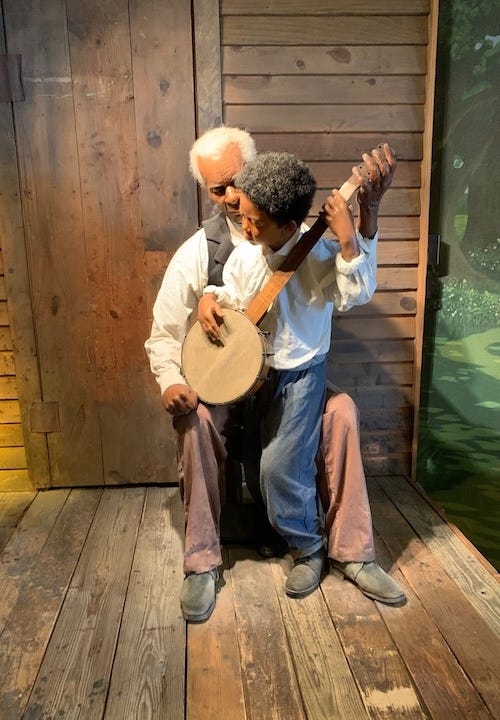

We saw a touching display of Black culture — and its complex resonances and distortions — earlier in our travels when we visited the American Banjo Museum in Oklahoma City. There, hundreds of banjos of every sort and style sparkle in the light. But the very first exhibit tells a powerful story, based on an 1893 painting by pioneering Black artist Henry Ossawa Tanner. It depicts an older man gently encouraging his young grandson to pick out a tune. The diorama, complete with an affecting sound track, stands in contrast, and rebuke, to nearby images of the appropriation of the banjo, an instrument of African origin, by white “minstrels” in blackface, a theft that would continue for generation after generation. The final exhibit in the museum features Rhiannon Giddens and other Black artists who have reclaimed the banjo as their own legacy.

The Whitney Plantation, located between Baton Rouge and New Orleans, stands as a living memorial to Black lives in enslavement. Over years, and with great investment and dedication, the plantation has gathered buildings and artifacts to tell the story of a plantation from the perspective of Black people. Whitney has set an example for other plantation sites to follow, which many have, with varying degrees of enthusiasm, skill, and commitment.

The Whitney strives to acknowledge the full humanity of the people held in slavery. At the outset of the tour, guides stand before a wall bearing the names of the enslaved people who lived and labored on the land.

A relocated slave cabin gains poignancy from models of two young children on the porch.

A monument to the German Coast Uprising of 1811, the largest revolt of enslaved people in American history, shocks visitors with heads on posts, showing the way the dead were displayed at the time of the failed rebellion. Each bears a distinctive Black face, emphasizing the humanity of those who risked their lives for freedom as they marched toward New Orleans.

At the end of the tour, a set of monuments inscribe the names of those enslaved in Louisiana from the first slave ships to 1820. The installation, appropriately, is named in honor of Gwendolyn Midlo Hall, creator of the Louisiana Slave Database, and a pioneering Louisiana historian who devoted decades to the work.

The Whitney Plantation has set a high standard for other plantation museums, but the physical climate there is working against the preservation of both structures and memory. The very heat and humidity that allowed sugar cane to be grown in Louisiana threatens fragile historical structures. In 2021, a hurricane destroyed slave cabins at the site.

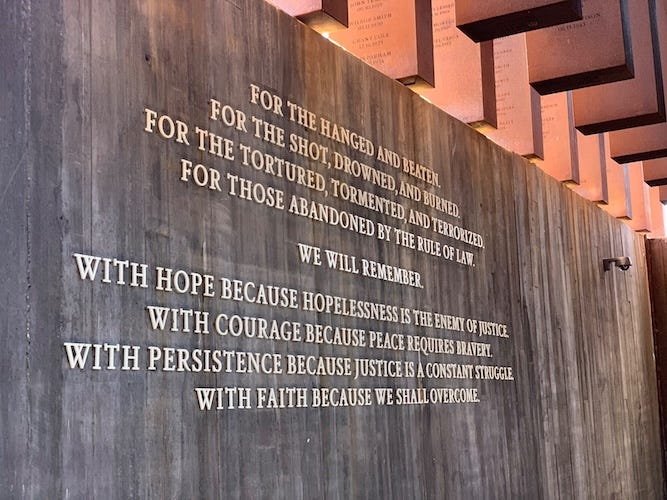

After our experience at the Whitney Plantation, we traveled to Montgomery, Alabama, to visit the Legacy Museum. It tells the story of Black Americans “from enslavement to mass incarceration,” focusing on the great wrongs perpetuated against people of African ancestry over centuries. Digital maps, video, and massive displays of words and images dramatize the injustice and suffering that Black Americans have endured, survived, and triumphed over.

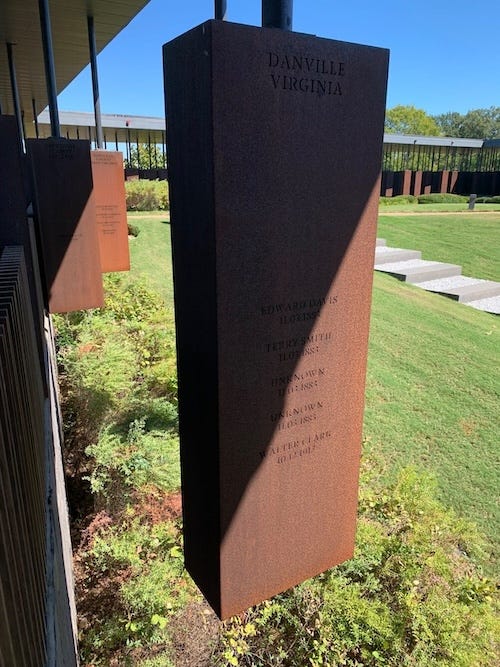

The nearby memorial to the Black people lynched in the decades after emancipation stands as one of the most impressive monuments in the nation. Its rusted steel plates carry the names of people unlawfully killed all across the United States.

Within the memorial, words declare its purpose and its effect.

As we worked our way back to Virginia, we thought about the legacy of slavery closer to home. Abby and I live about 10 miles from Monticello, the mountain behind our house prominent in the view from Thomas Jefferson’s “little mountain.” Over the years, I have watched, and sometimes worked with, Monticello staff as they labored to restore the presence and humanity of the enslaved people who lived there. When we first arrived in Virginia, in 1980, guides at Monticello still spoke of “servants” on house tours, and seemed annoyed by any mention of Sally Hemings, who was rumored to have borne children with Jefferson. Today, as the result of dedication and determination by many people, Monticello has reconstructed Mulberry Row, where enslaved people lived and worked. Sally Hemings, as shown by exhaustive research, did indeed bear children with Jefferson and that fact is openly acknowledged on tours. The windowless room in which she lived now bears her silhouette.

This is progress. In all the places we visited, we found people of many backgrounds giving their time, money, and attention to learn about Black history. The labors of descendants, historians, museum professionals, sculptors, artists, archivists, architects, and visionary leaders are being repaid, now and for generations to follow.