Howard Zinn wrote one of the most popular books on American history ever. A People’s History of the United States has sold an astonishing two million copies since its first publication in 1980. The success of the book can also be measured by the way that it spawned a new genre of “people-centered” renditions of history. Zinn’s approach to history essentially inverted the traditional approach that placed the rich and powerful, along with the institutions they governed, as the central motors in the development of society. It was history told from above. Alternatively, Zinn championed an approach to history from the bottom up or from the perspective of “the people.”

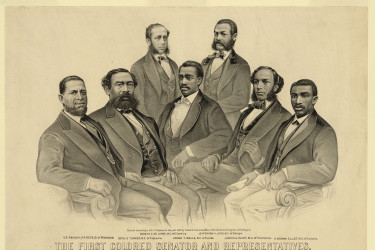

The implications were radical. History was no longer seen as reducible to the expressed will of the elite but as a process elucidated through the actions of ordinary people in their confrontations against the powerful. To tell history from the perspective of the oppressed and marginalized was to recognize that to the degree there has been any progress in the United States, it has come from the struggles of regular people demanding rights, justice, democracy.

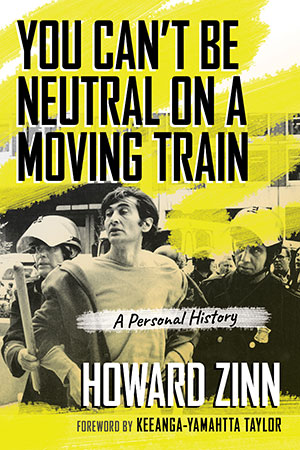

This was not a scholastic endeavor for Zinn, even though he was a professor of history. But history was not academic exercise; it was a means to make sense of the world we live in and, if necessary, a guide to action. Zinn, a prolific writer and scholar, tore down the wall intended to separate activism—or partisanship—from the professed objectivity of scholarship. Instead Zinn told his students that he did not “pretend to an objectivity that was neither possible nor desirable. ‘You can’t be neutral on a moving train,’ I would tell them. . . . Events are already moving in certain deadly directions, and to be neutral means to accept that.”

Zinn eschewed neutrality, choosing to write reports, news stories, and multiple books from the perspective of the movements that he was active in. Prolific and without pretension, Zinn chronicled the civil rights and anti-Vietnam War movements for the general public. His writing exposed the broader world to the realities facing ordinary Black people across the South while also challenging the assumptions that the United States, by the sheer volume of its bombing campaign in Vietnam, could impose its will on that tiny country.