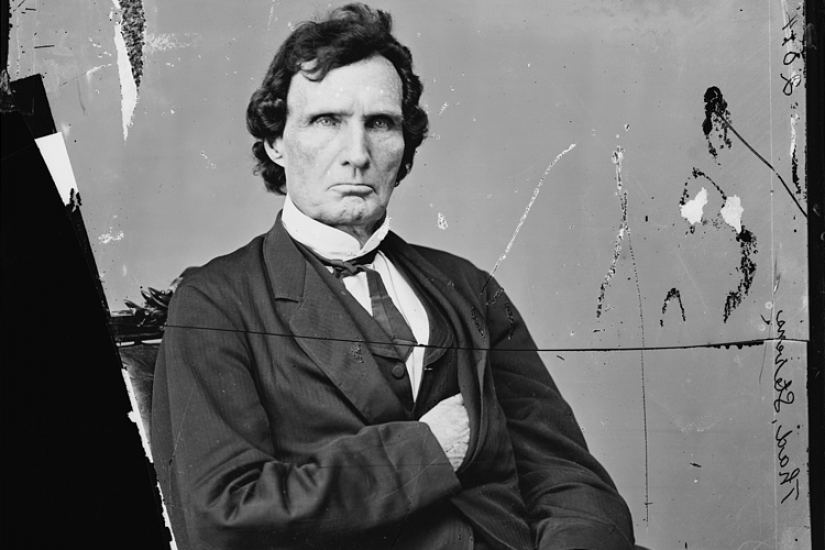

If French Jacobinism had a corollary during the Second American Revolution, it was embodied by Thaddeus Stevens. A leading abolitionist in the House of Representatives during the antebellum period, the man who came to be known as the Great Commoner emerged during the Civil War as de facto leader of the Radical Republicans and a standard-bearer for the causes of emancipation, the enlistment of black soldiers, African American suffrage, and land reform. Exploiting wartime conditions to pursue a radical revolution capped by a confiscation policy that would redistribute Confederate land to formerly enslaved people, Stevens understood as few others did that uprooting slavery meant overthrowing the South’s economic system and challenging property rights beyond property in human beings.

But as the most controversial statesmen of his era, Stevens’s popular reputation has fluctuated widely, falling and rising in inverse proportion to Jim Crow and the Lost Cause. He was for a century one of the most reviled figures in American history. Conversely, when civil rights and justice movements have surged, his popular reputation has consistently been rejuvenated.

In that sense, Bruce Levine’s Thaddeus Stevens: Civil War Revolutionary, Fighter for Racial Justice provides an anticipated and most welcome update of this anti-racist champion in the age of Black Lives Matter, falling Confederate monuments, and rising calls for transformational policy.

The Making of a Radical

Stevens’s path to wartime racial and economic justice pioneer was a lifetime in the making, and Levine diligently tracks his subject’s decades-long evolution, exploring key developments that other biographers have neglected. Born in 1792, Stevens acquired his progressive bent from his relatively poor upbringing in the small farm and mutual assistance culture of rural Vermont, where he was influenced by his Baptist faith, as well as early exposure to classics and Enlightenment readings. By the mid-1830s, and now representing his adopted state of Pennsylvania in the US House of Representatives, he had developed into a dyed-in-the-wool abolitionist.

As an activist Whig and gifted parliamentarian, Stevens was a tremendous advocate for universal public education and infrastructural improvements. His political record was not spotless, including support for voluntary colonization as an alternative to emancipation, a sojourn with nativists, and retaining personal doubts about universal suffrage. But Stevens’s early uncompromising approach toward the growing “Slave Power” — being far ahead of public opinion and his own party — established a pattern.

Stevens’s egalitarianism soon became inseparable from his understanding of free labor. Rather than counterposing Stevens’s economic position to his social idealism, as other biographers have, Levine reminds readers that free labor economics and social leveling were facets of a single worldview.