U.S. history is a strange, exceptional field of play where, to paraphrase Garrison Keillor’s famous sign-off from Lake Wobegon, all the revolutions are strong, all the revolutionaries are kind, and even the civil wars are above average.

In the orthodox telling, there was only one revolution that mattered, after all. The fact that American revolutionaries won their independence in part because the French intervened in their British civil war has often been narrated as at most a useful irony. Certainly Africans or Natives had nothing to do with it, except as desperate fighters for their own marginal purposes: defined out of the story partly because they lost but mostly because, well, they were defined out of the story. Yet the century-long debate between “Progressive” (read: radical) versus “Whig” (liberal and conservative) historians about whether ordinary white people benefitted or whether elites did has begun to seem almost beside the point: there was more at stake for others than republicanism or nationhood.

The certainty that “the people” and their liberties triumphed and set the stage for future progress doesn’t seem sufficient as history anymore. Casting the U.S. Civil War as a second good revolution—a resolution of unfinished business that finally ended slavery (how stubborn it proved!) and created a real nation-state—leaves many questions unanswered. If Revolutionary-era ideas and Civil War identities are so powerful and bend so decisively toward justice, why are the wrong ones winning? No wonder the settler revolutionaries of 1776 realized that the first priority was spin—or as Thomas Jefferson put it so delicately in the Declaration of Independence, “a decent respect for the opinions of mankind.”

The United States claimed to be the first self-determined nation, a model for anti-monarchy and anti-colonialism. In a nationalist, liberal world, this was everything, and in particular a beacon against reaction. For socialists it was primitive, if not worse than nothing: a bourgeois mirage, or just an exception (the too-often unappreciated subtext of the famous question, “Why is there no socialism in the United States?”). Marxists have long kept a cordon sanitaire around the American Revolution, focusing instead on the resulting nation’s imperialism; their inquiries were dominated by the French, Russian, and decolonizing revolutions. The real problem may have been the inability to see counter-revolution as something that could happen here.

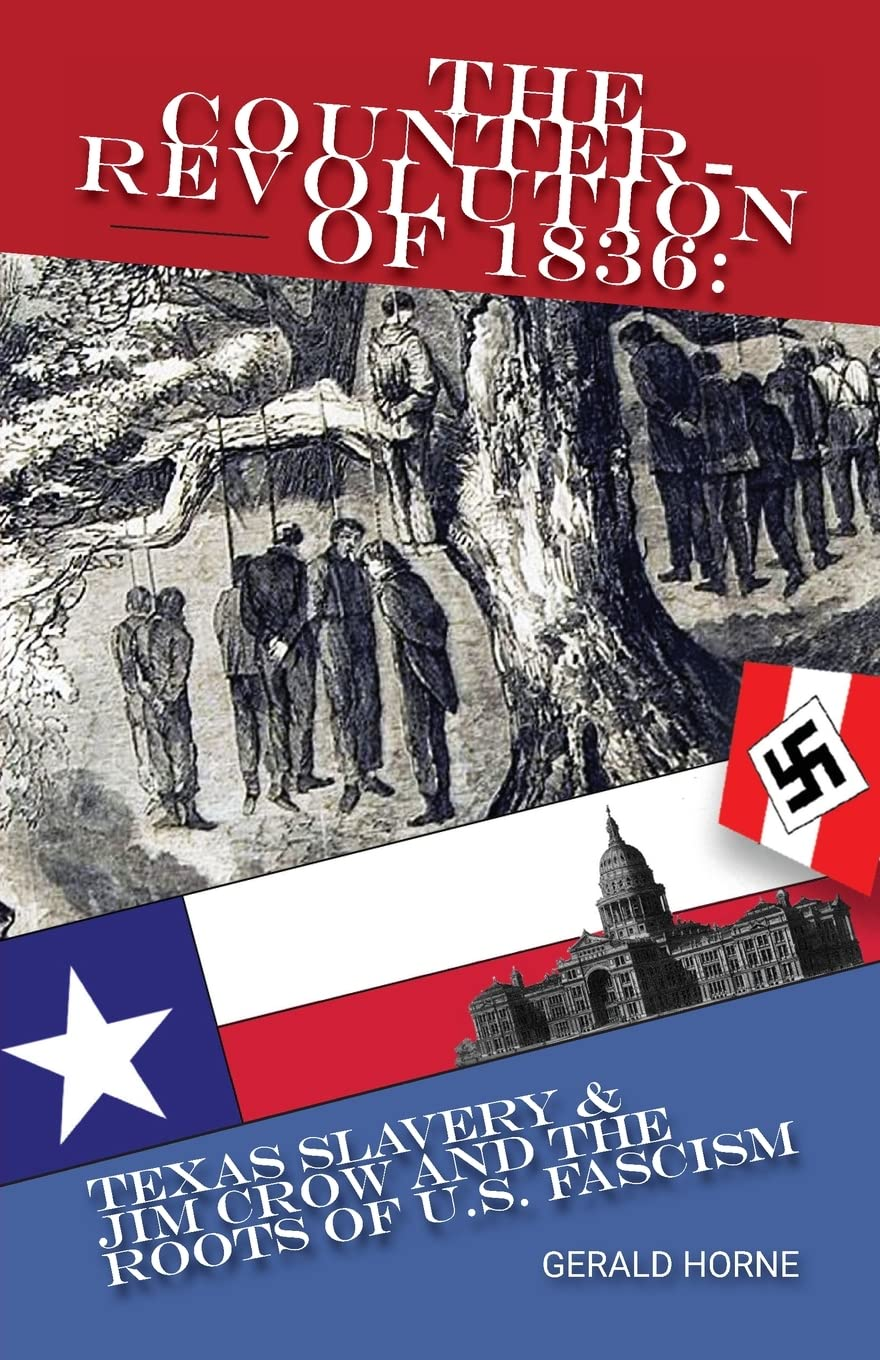

That tide has slowly been turning. For two decades Gerald Horne, the Moores Professor of History and African American Studies at the University of Houston, has been building a well-documented argument for rethinking the entirety of U.S. history in terms of empires and insurrections and counter-revolutions. With his latest book, The Counter-Revolution of 1836, he has given us a distinctive magnum opus: the longest and perhaps most challenging of his many books. Horne places Texas and its revolution at the center of the national story that now stretches, in his series of studies, from the sixteenth to the twentieth century, with occasional instructive asides about how unsurprising the right-wing resurgence of our era ought to be to anyone with an unblinkered knowledge of history. Instead of a sanguine trajectory from Jamestown or Plymouth to Obama, it’s the story of Christopher Columbus to Trump, with the loss of redemption that this should imply and then some.