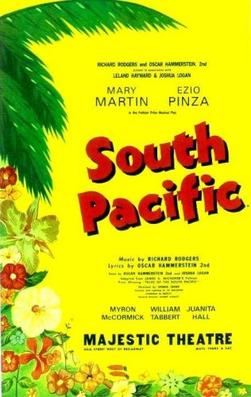

In South Pacific (1949), that piece of hoary Americana beloved by community theater directors everywhere, Nellie Forbush must overcome one obstacle before winning the man of her dreams and ushering in the obligatory happy ending of a typical Rodgers and Hammerstein musical. A rival suitor? Domestic obligations prevailing over her heart’s desire? A pile-up of comic misunderstandings? No, the impediment standing in the way of her happiness is rather more primal: The apple-cheeked, all-American heroine is a racist, and until she can overcome her horror at the discovery that her dreamboat French suitor, a French widower of impeccable taste and sensitivity, has fathered two mixed-race children by his deceased Polynesian wife, she’s going to deprive herself of the glorious romantic finale that the audience has every right to expect. Maybe South Pacific isn’t quite so hoary after all.

I hesitate to put forward Oscar Hammerstein II as an exemplar of mid-century liberalism, and indeed he has been judged and found wanting by progressive theater critics of our time. Writing in American Theatre, Sravya Tadepalli claimed that the similarly loaded King and I “reeks of white savior-ism and an imperialist gaze.” The title of Tadepalli’s 2021 article gives the game away: “Can The King and I Be Decolonized?” No, it can’t. As for Hammerstein’s earlier Carmen Jones, his rewriting of Bizet’s Carmen with a wholly African-American cast and setting, many such critics consider it simply beyond the pale. “The show is a figment of Hammerstein’s imagination,” wrote Hilton Als in The New Yorker (2018), “and he is to blame for what’s stupid about it.”

And yet I do put forward Oscar Hammerstein as an exemplar of mid-century liberalism. His critics are at least partly correct. You don’t have to be in love with the jargon of woke progressivism to see the manifest limitations of Hammerstein’s sociopolitical worldview, with its unavoidable suggestion of noblesse oblige. Indeed, those limitations were apparent as long ago as 1955, when James Baldwin savaged the movie version of Carmen Jones for its “really quite helpless condescension” and its “total divorce from anything suggestive of the realities of Negro life.” Further, Baldwin wrote in “Carmen Jones: The Dark Is Light Enough,” “the movie cannot possibly avoid depending very heavily on a certain quaintness, a certain lack of inhibition taken to be typical of Negroes.”