Shawn Gude: Let’s talk about the ’63 March on Washington. Obviously, the most remembered part is Martin Luther King’s “I Have a Dream” speech. But that omits a lot about the event. I was wondering if you could talk about the march, which explicitly paired the fight against Jim Crow with the fight for economic justice.

William P. Jones: There are a couple things I would emphasize. One is the painstaking attention to the message — how it was articulated and how it would be projected. Bayard Rustin insisted they get this $20,000 sound system because he said that if people in the back can’t hear, they’re not going to be engaged. They had this whole security system within the march to try to dissuade people from getting into arguments and fights — the Nazi Party was there, taunting people, trying to cause trouble. So there was this very meticulous attention to getting the message out and preserving the image of the march.

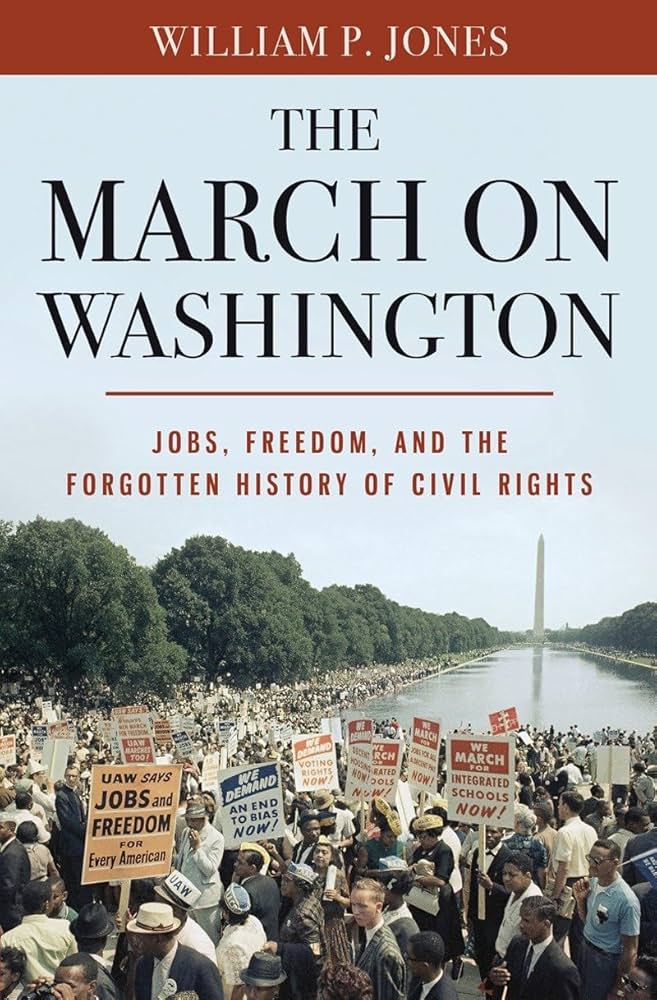

Just getting people there was a tremendous endeavor. It was a weekday, so people had to take off work. Most people came from big Northern cities, and the unions often would hire trains. For most people, they were on the train or the bus overnight.

King’s speech came at the end of this really long day. He was purposely trying to get people’s spirits up, trying to rally people before the end. What’s tragic about the way we remember the march — because they went to such extents to make sure everybody knew what the march was about — is that King’s was the least specific speech about the goals of the march.

Flyers were printed up with instructions on attending the march, then, really boldly, the demands of the march. Then they read out the demands at the beginning and at the end, and the speeches were really specific about the connection between economic justice and racial equality.

There was a lot of grumbling after the March that the media didn’t pay attention to the economic demands, but at the moment, it was pretty unavoidable. The full thing was broadcast on radio and on television. Newspapers were there. It’s only over time that the image of the march was narrowed down, and that colorblindness was seen as the main goal of the march, which it was not at all.

Shawn Gude: I was kind of astounded to learn in your book that in the spring of 1964, several months after the march, and with the civil rights bill still stuck in Congress, Randolph called for what was effectively a general strike. Could you talk about the aftermath of the march, and how the Civil Rights Act of 1964 was finally passed?

William P. Jones: A couple things about the Civil Rights Act are important to remember. John F. Kennedy introduced that bill in the summer of 1963, and he was adamant that it should not have the fair employment provision. He thought that would alienate Northern Republicans who might otherwise support a bill focused on voting rights, integration of schools, etc. An important part of the march was that they wanted to add an Fair Employment Practices Committee provision to the bill. And that’s what the march did.