Opening up a box of tantalizing what-ifs, Nussbaum consistently finds that the path history took was the best possible one. Lewis’s and King’s speeches, for instance, turn out perfectly balanced for “the needs of the moment”—though we can’t know what (perhaps more powerful?) impact a different balance might have produced. Humbly disclaiming historical authority, Nussbaum accepts the liberal understanding of history as an exalted (if not otherworldly) force of its own: “History—with a capital H.” In this providential outlook, all events, even seemingly evil ones, ultimately forward a story of progress, and the great must at times rise above ordinary mortality with the promise of vindication by history. It’s an assumption of an “arc of history” (President Obama’s pet phrase), itself propagated across time on the wings of momentous speeches, inspiring moral courage but also moral recklessness, as I’ve described in my recent book Time’s Monster.

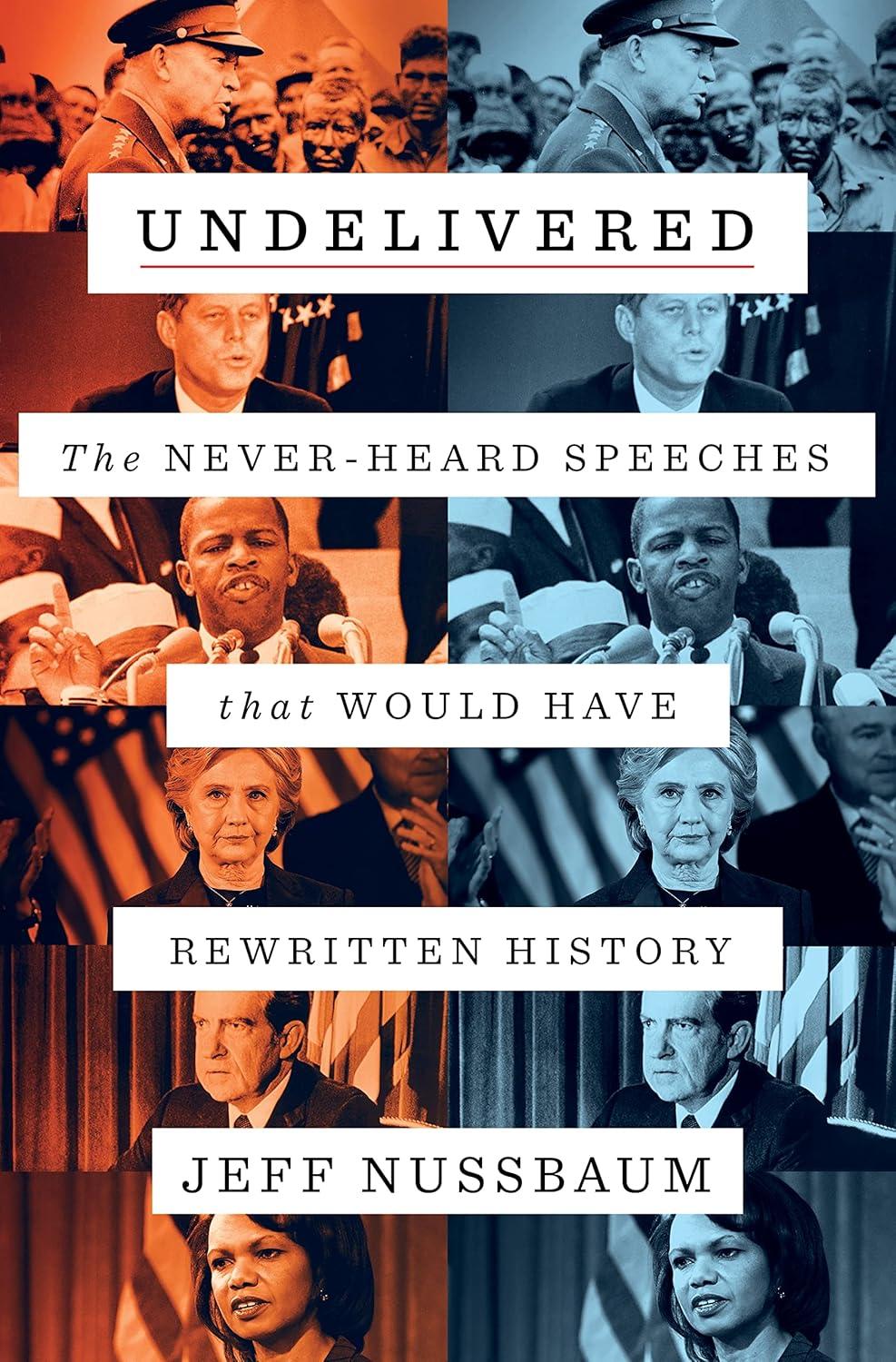

The very idea of the speaker as the fount of political action, inspiring ordinary people to act, stems from this liberal historical imagination. Nussbaum’s “instinct about where to uncover a never-given speech,” depends on a narrow definition of what counts as a speech: These are famously undelivered speeches. The array of “occasions” for such speeches are events pre-invested with historical meaning (inauguration, commemoration, annual awards ceremony)—hence the presence of technological amplification (mass media like newspapers, radio, television) allowing the audience and a vaster remote audience to be addressed at once.

But these are merely the speeches we know went undelivered; what about the unknown undelivered speeches—all those “occasions” when we craft words, on paper or in our minds, but shrink from giving them utterance? Which of these numberless conceived but undelivered “speeches” count as likely to have changed history (even if our inability to voice them in that moment is itself a function of history)?

Certainly, in a world in which a historical imagination centered on great men and hinge moments of history deeply influences our understanding of our agency, the words of the great have outsize impact. But as one great man, Mahatma Gandhi, noted, the sustaining force of love—conveyed through everyday speech by ordinary people—routinely defuses would-be conflicts in a manner illegible to liberal conceptions of history. History is, in fact, the unceasing flux of life, a continual quarrel between ethics and circumstances that shapes the ends of each of our lives. Ordinary people routinely make history without inspiration from a podium, evident in Undelivered’s depictions of the crowds who time and again determine who can speak and what they can say. Speeches that matter include the exchanges integral to group activism, such as the addresses that daily fueled protest from 2020 through 2021 by Indian farmers—speech that merges with song, slogan, and poetry, that is entwined with action. The danger lies not only in listeners at speeches failing to recognize their agency, as Nussbaum warns, but in imagining their agency as purely reactive.