The true economic legacy of the Reagan years is an uglier practice: unionbusting, of the most brutal variety. To this day, commentators hail Reagan’s handling of the 1981 strike staged by the nation’s air traffic controllers as the defining moment of his fledgling presidency. Not only did the sudden dissolution of the strike—and the controllers’ union, the Professional Air Traffic Controllers Organization—seal the reputation of our first post–New Deal president as a bare-knuckles foe of liberalism’s most influential single constituency, organized labor; the PATCO episode also became mythologized as the landmark case of Reagan’s signature leadership style, an instinctive commitment to “stand firm and stand for the truth,” as GOP presidential candidate and Reagan disciple Newt Gingrich rhapsodized in a primary debate last year.

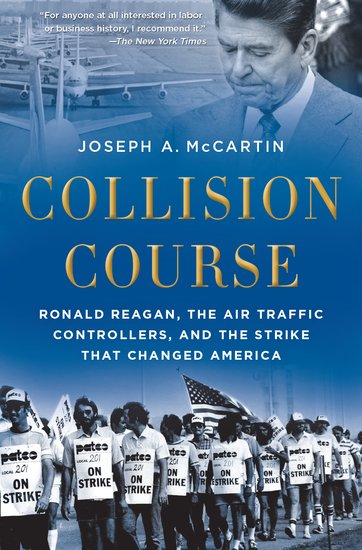

But like most political decisions, Reagan’s sacking of PATCO wasn’t so much a pure expression of composure and principle as it was the unanticipated outcome of a convergence of far messier, contingent and nonideological forces. Joseph McCartin, a professor of US history at Georgetown University, patiently lays out the full background and aftermath of the PATCO tragedy in Collision Course, an absorbing, detailed and shrewdly observed chronicle of the strike and PATCO’s unlikely rise and fall.

The first of the saga’s many related ironies is that the nation’s air traffic controllers never enjoyed the legal right to bargain collectively with their employers in the government, let alone to stage a mass walkout from their posts. Government employees had the right to form unions only within tightly circumscribed limits, which had been laid out in Executive Order 10988, signed by John F. Kennedy in 1962. As McCartin notes, Kennedy’s order was a rear-guard action, urged on him by advisers who “feared that Congress might enact a bill that gave workers too many rights and unions too much power”—a strategic calculation that, viewed in the resolutely corporate cast of Congressional politics circa 2012, sounds like a transmission from a faraway galaxy. Beyond acknowledging that federal workers could use union representatives to air grievances about working conditions, the order barred unions from negotiating wages and hours, and failed to establish an agency to oversee and arbitrate even the narrow sphere of grievances employees were permitted to raise. Kennedy’s labor secretary Arthur Goldberg and domestic adviser Daniel Patrick Moynihan pushed hard for the order to include provisions for an official negotiating framework to handle union demands; as Moynihan argued at the time, “if we do not grant this to the unions, in lieu of the right to strike, it is to be doubted that we will accomplish much. Indeed, unless we provide some way out of deadlocked negotiations, it would seem rather questionable to start down this road at all.”