The story of the Jews was extremely important to Hurston, as important as her mission, far better known, to preserve and to celebrate the style, speech, and folklore of the African diaspora—the culture of what she called “the Negro farthest down.” That mission yielded two works of cultural anthropology, “Mules and Men” (1935) and “Tell My Horse” (1938), and the novel on which her reputation is built, “Their Eyes Were Watching God” (1937).

But Hurston devoted a big portion of her literary career—which stretched from 1921, when she published her first short story in a Howard University literary magazine, to 1960, when she died—to trying to write a history of the Jews. This meant, essentially, rewriting the Bible. It was a colossal ambition, and it is striking, although maybe not surprising, how little attention the effort has received in the critical literature on Hurston, of which there are now shelves full. Between 1975, when she was “rediscovered” by Alice Walker, and 2010, more than four hundred doctoral dissertations were written on Hurston. “Their Eyes Were Watching God” has sold more than a million copies, and Oprah Winfrey produced a film adaptation. In Hurston’s lifetime, the most any of her books earned in royalties was $943.75.

Hurston was a grapho-compulsive. In addition to four published novels and three works of nonfiction, which include an autobiography, “Dust Tracks on a Road” (1942), she wrote short stories, poems, plays, essays, reviews, and articles. She also staged concerts and dance performances. By the time she died, she had published more books than any Black woman in history.

And she was a tireless correspondent, possibly because for much of her life, despite three somewhat mysterious marriages, she lived alone. An excellent edition of the correspondence, edited by Carla Kaplan, contains more than five hundred letters, and, since Hurston was not shy about writing to people she had never met (she once asked Winston Churchill to contribute an introduction to one of her books; he politely declined, citing poor health), it is believed that there may be hundreds more letters still out there, no one knows where.

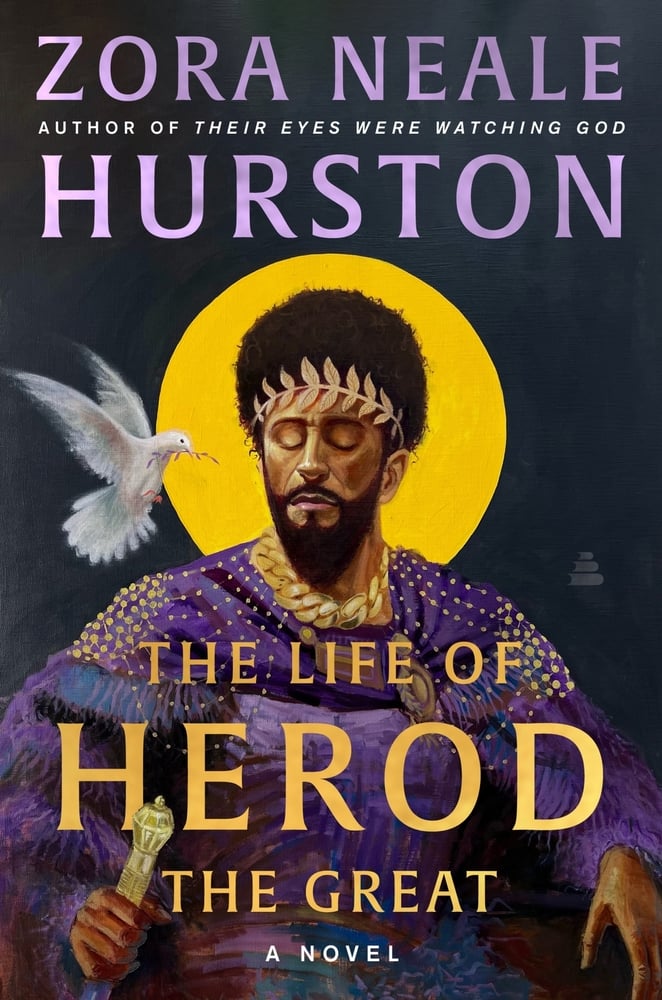

Like most freelance writers, she had a fairly high kill rate. Some pieces were rejected or didn’t work out or for some other reason never appeared in print; her autobiography was expurgated by her publisher; and she wrote some or all of at least five novels that were turned down. Only one of these, “The Life of Herod the Great,” survived in typescript—the others appear to be missing completely. “Herod” has now been published by Amistad in a volume edited by Deborah Plant, an independent scholar. Plant is also the author of a critical biography of Hurston, published in 2007, and the editor of another Hurston manuscript, “Barracoon: The Story of the Last ‘Black Cargo,’ ” which was published in 2018.