It was only in the 19th century that the modern phenomenon of pet ownership emerged. As people moved to cities in the wake of the Industrial Revolution, many adopted a new form of the rural tradition of animal-keeping by bringing a dog or cat into the home. “For the first time, you get people living in big cities with animals in confined quarters,” Koudounaris says. “This naturally changed the relationship people had with those animals—not just physically, but also emotionally.”

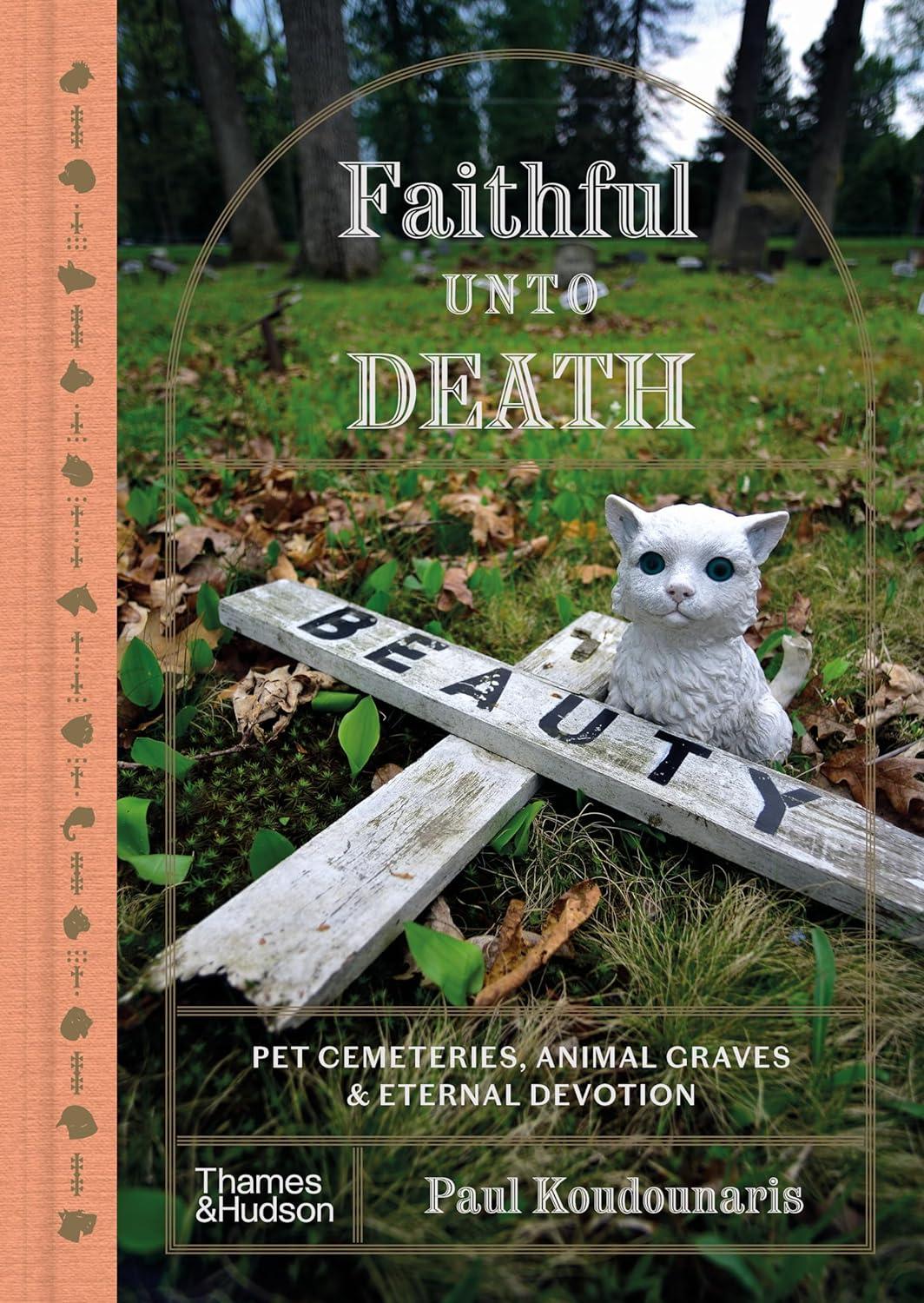

Society at large soon began to reflect this changing relationship. Dog breeds, especially of the smaller varieties, began to proliferate. The first dog-grooming salons opened in London, and in Paris, fashion designers began creating canine lines of clothing with accompanying look books. These cultural developments coincided with the rise of animal welfare organizations, starting in England with the 1824 founding of the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals. The advent of pet cemeteries “went along with all these other revolutionary acts,” Koudounaris says. “They affirmed this idea that a pet that lived as a family member and that loved us and has been loved like a family member deserves a good death.”

After Cherry’s burial, pet cemeteries began to spread in the United Kingdom and Europe. But even as the idea of burying animals gained more acceptance, cemeteries created for this purpose were sometimes met with pushback. In 1899, for example, when the first public pet cemetery opened in the Paris area—complete with a potter’s field for animals—the Catholic Church expressed concern that it may too closely resemble a human cemetery. “To placate the Catholic Church, the cemetery owners had to make an agreement that there would not be any religious symbols on the graves,” Koudounaris says. Even today, he adds, he was unable to find any Christian iconography in the still-active Cimetière des Chiens.

In 1896, the first U.S. pet cemetery—which is also still active—opened in Hartsdale, New York, in Westchester County. From there, “this really became an American story,” Koudounaris says. “There are now more pet cemeteries in the United States than in the rest of the world combined, and there are a staggering number of different types.”

Around the U.S., Koudounaris found, for example, pet cemeteries dedicated to specific types of hunting dogs, to military pets and to police dogs. “What makes the United States so fascinating is there’s a polygenesis,” Koudounaris says. “While pet cemeteries are starting on the East Coast with the traditional European-type model, they’re also being born in a whole lot of other places in entirely different forms.”