“Here we have a man whose job it is to gather the day’s refuse in the capital,” wrote Charles Baudelaire, invoking the ragpicker, a new type on the streets of his native nineteenth-century Paris. “Everything that the big city has thrown away, everything it has lost, everything it has scorned, everything it has crushed underfoot, he catalogs and collects.”

Buried in Baudelaire’s descriptions of ragpickers are processes that historians have recently laid bare. With industrialization came the rise of consumer culture, and with consumer culture came the rise of disposal culture. Add unfettered fossil fuel use and the invention of single-use plastics and we arrive at the ragpickers of today: people in Indonesia climbing mountains of trash, or children scavenging for survival in the slums of Delhi or Manila or northeastern Brazil. Consumer lifestyles in high-income nations have clogged the oceans with garbage and broken our recycling systems. Only 9 percent of the world’s plastic waste is recycled, according to the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, but plastic consumption is on track to triple by 2050. Running out of places to put our daily detritus, the United States and the European Union export hundreds of millions of tons of garbage each year to poorer nations where it is landfilled, littered, or burned.

In two new books, the rise of recycling is a story of illusory promises, often entwined with disturbing political agendas. In Empire of Rags and Bones, Anne Berg, a historian at the University of Pennsylvania, examines one of the first modern recycling systems: the “waste regime” of Nazi Germany, where planners and engineers devised programs to recycle metal, rags, and paper; repurpose wires, cables, and railroad equipment; compost kitchen scraps; and collect old shoes, utensils, and junk—all in the service of a genocidal war.

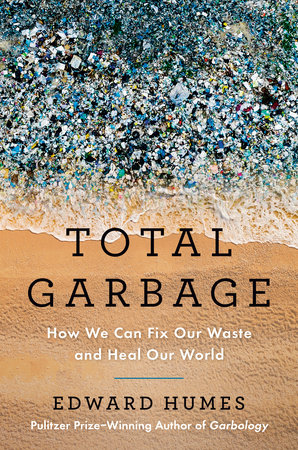

In Total Garbage, journalist Edward Humes picks up the story of recycling from the postwar era to the present. His dive into the teeming wastes and faltering waste management systems of the United States shows that most recycling is a charade, a form of carefully constructed greenwashing that belies the fact that most postconsumer waste, including packaging, clamshells, films, pouches, boxes with windows, bags, and food containers, was never designed to be recycled.

Rather than being a virtuous act or an effective practice, recycling has been a feature of destructive systems that exploit labor and natural resources. We need a better way to think about our trash, and even more so, our consumption.