Many people equate “historical knowledge” with nothing more than facts, names, and dates. So if a five-inch handheld device can tell you faster than you can recall when Jamestown was founded or what the Code of Hammurabi is, what’s the point of studying history at all? This question—a logical one for those who’ve sat through one too many bad history classes—frames Stanford educator Sam Wineburg’s forthcoming book from the University of Chicago Press, Why Learn History (When It’s Already on Your Phone). (Editor’s note: AHA executive director James Grossman contributed a blurb for the book.) As Wineburg explains to Perspectives, “The idea that history has a way of thinking, and that it can be profoundly useful for approaching everyday life, is something that is in the awareness of some excellent instructors, but escapes many teachers of history.”

Of course, Perspectives readers might say that they can easily respond to Wineburg’s question. After all, advancing the value of historical thinking is one of the AHA’s principal charges. But Wineburg’s mission is not simply to help teachers in their classrooms or to advocate for history. It is to sound alarm bells about the profound information confusion brought on by the Internet in today’s society. Gesturing to his smartphone, Wineburg tells Perspectives, “This device is in many ways more powerful than any library we have had from 1900 to 1970.” The problem, though, is that this library lacks any semblance of gatekeeping. He urges teachers—and those who are training future educators—to ditch the “read-the-chapter-and-answer-the-questions-in-the-back pedagogy” that has stifled critical thinking for decades. Instead, he asks teachers to give students the tools they need to sort out fact from fiction in the digital age.

Today’s students might be “digital natives,” but that doesn’t make them responsible consumers of digital information. Between January 2015 and June 2016, Wineburg’s research team evaluated thousands of American students’ ability to judge web sources. What they found was “bleak,” writes Wineburg. Eighty-two percent of students “couldn’t distinguish between an ad and a news story,” and less than 10 percent of college students could identify partisan leanings on websites. Even more disturbing was the finding that teachers, too, sometimes unintentionally directed students to faulty or biased online resources. In one instance, California middle school teachers handed out a document for an assignment that came from an anti-Semitic, Holocaust-denying Australian website.

In his book, Wineburg lays the blame for this sorry state of affairs on the standard American educational system, which he says has been “stuck in the past” for decades, neglecting to teach foundational skills that would help students confront these problems. He attacks resources and institutions that have long been popular among many history educators—standardized testing, the Department of Education’s Teaching American History initiative, and Howard Zinn’s A People’s History of the United States—as having “relegate[ed] students to roles as absorbers, not analysts of information.”

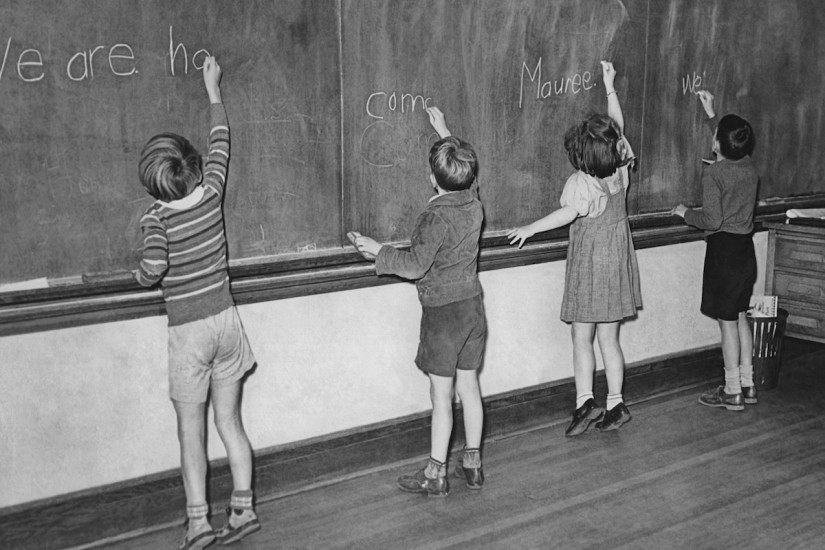

Wineburg does more than just eviscerate modern instruction, however; he also offers some semi-encouraging notes—students today are no less intelligent than their grandparents were, he writes. Despite popular and often politicized claims that US history education has declined from a past golden age, Wineburg cites evidence that standardized history test results have remained steady over the last century. Kids from the “Greatest Generation” confused 1492 and 1776 in the same way that their modern-day counterparts do. Wineburg argues that this “kids these days” mentality simply distracts us from the real problem. He writes, “Test results over the last hundred years point to a peculiar American neurosis: each generation’s obsession with testing its young, only to discover—and rediscover—their ‘shameful’ ignorance.”

According to Wineburg, the issue is not that students are ignorant of names and dates. In fact, as he points out, even the most accomplished specialists in the discipline could flunk a multiple-choice test on an area of history they are unfamiliar with. It’s more of a tragedy, he argues, that students are made to memorize facts instead of learning the critical-thinking skills that equip their minds to discern context, sniff out biases, and employ reasoned skepticism when evaluating sources. And standard-issue history textbooks don’t provide these skills, either. Burdened under the yoke of Scantrons, wasted tax dollars, and turgid textbooks, the vast majority of students are ill-prepared, he writes, to face the challenges of the digital age.

In the meantime, “the Internet has obliterated authority,” Wineburg thunders in his book’s introduction. Anyone with an Internet connection can write “history,” publish it on the web, and claim it as fact, no submission or peer-review process necessary. Wineburg challenges educators to think about how their instruction needs to change in order to meet these challenges. “Historians by and large still treat the world like a print world,” he comments. “My response to them would be—do you still wait in line at the bank to go deposit your checks? Do you still have a thick stack of maps in your glove compartment that you would take to an unknown destination? And if you do, I can bet that the notes for your lectures are dog-eared yellow.”

The book describes a recent research project that sheds light on how far behind historians actually are. Wineburg convened history PhDs and professional fact-checkers (such as those employed by newspapers) to evaluate the credibility of information found on the pages of two organizations’ websites: the American College of Pediatricians and the American Academy of Pediatrics. His team observed that historians read the websites “vertically,” staying on the page for the entirety of the exercise as if it were a lone print source. Many of the historians deemed the American College site more trustworthy, reasoning that it contained references to credible professional journals. Seemingly lost on them was the notion that in the absence of print oversights and safeguards like peer review, these references could have been completely falsified. On the other hand, the professional fact-checkers worked “laterally,” opening up multiple browsers immediately to cross-reference other sites with the originals. They correctly discerned that the American College of Pediatricians was a reactionary splinter group of doctors who opposed adoption by same-sex couples, and who had been accused in the past of distorting published research findings.

Confronting the reality that even professional historians can make mistakes reading sources on the internet, Why Learn History provides clear advice to history teachers about what they can do to improve digital media literacy. First, Wineburg says, show students “how the game is played.” Instead of giving students the old “read the textbook” spiel, he advises teachers to use the textbook as a springboard for introducing alternative viewpoints. He asks them to give students exercises that involve mining and evaluating web sources like fact-checkers—teaching them to read laterally, not vertically. And he urges teachers, at the end of the day, to make sure to assess student progress in order to figure out what’s working and what’s not. Wineburg himself is starting a new project that encourages this model. Over the next two years, along with his team at the Stanford History Education Group, he plans to develop educational materials and professional development resources aimed at helping students navigate digital information.

But teachers can’t help their students spot flawed or fake information in cyberspace if they aren’t being taught how to do it themselves, Wineburg says. He notes that historians, graduate programs, and professional organizations have woefully undervalued the scholarship of teaching and learning. “We are not preparing the majority of graduate students for their primary mission,” Wineburg says, “which is not as the authors of historical monographs, but as teachers in community colleges, at second- and third-tier institutions, at a whole variety of places where one must develop expertise in the classroom.”

Wineburg also laments the ways in which history education is lagging far behind the sciences. He points to one of his colleagues at Stanford, physicist Carl Wieman, who pioneered the integration of student response systems called “clickers” in science classrooms. Wineburg finds it absurd that he has had to explain to audiences of historians what clickers are, despite the fact that the technology has revolutionized teaching in introductory science classrooms at state universities. He tells Perspectives, “I cannot give you an example more chilling about how history as a profession is stuck in a procrustean bed and practically unable to move.”

Despite these sobering revelations, Why Learn History signals that improvement is well within reach. Says Wineburg, “I think that historians have a crucial role in helping young people navigate the shoals of unreliable, solid, false, true, dependable, and rickety information that confront us. The connections between the historical thinking that we’ve developed in print sources, and the kind of historical thinking that we need to engage in digital sources, those connections are inchoate but are begging to be developed.” Wineburg emphasizes that it is educators and educators alone who have the power to right past wrongs. After all, publishers, editors, and librarians are no longer the shepherds of information. “The future of the past may be on our screens,” Why Learn History concludes. “But its fate rests in our hands.”