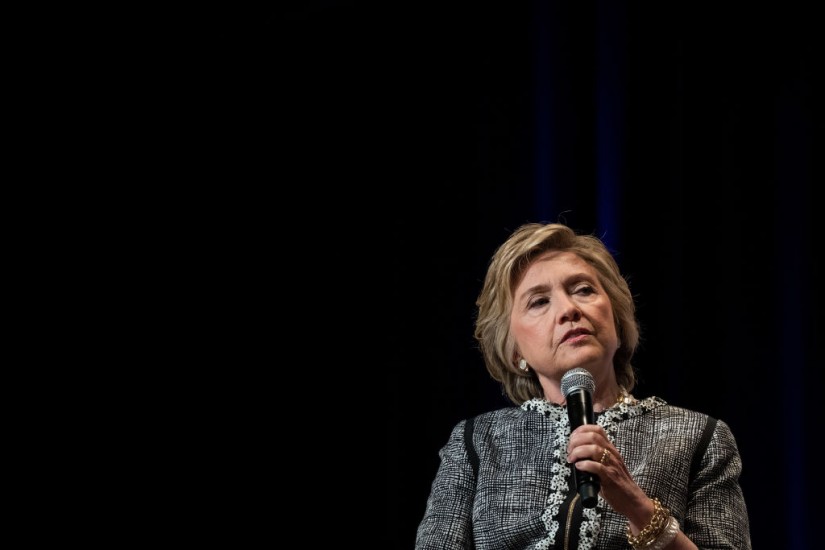

Hillary Clinton is by no means the first major party nominee to lose a close presidential election and find herself the subject of continued scrutiny months later. What McCullough observed of Nixon has been true of candidates before and since: Once in the public fray, it’s difficult to make a graceful transition to private citizen—even in defeat.

But that’s where the precedent ends. Like those who came before him (Henry Clay, Thomas Dewey) and those who followed (Hubert Humphrey, Gerald Ford, Al Gore), in defeat Nixon remained a widely credible figure: respected by the political establishment, popular in his own party and a member in good standing of the country’s small community of statesmen. The same has not, thus far, been true of Hillary Clinton, who lost the presidency to Donald Trump despite handily defeating him at the polls and winning more votes than any presidential candidate in American history ... save Obama.

Unlike every other near-miss candidate, Clinton remains a pariah among a large portion of the population: widely disparaged by pundits, blamed by some on the left wing of her party for Trump’s victory, despised by Republicans and many independents. Her singular fate—basically unprecedented in American history—tells us far more about the state of contemporary politics and journalism than it does about Hillary Clinton, whom history may very well judge with greater retrospection and consideration than her contemporaries.