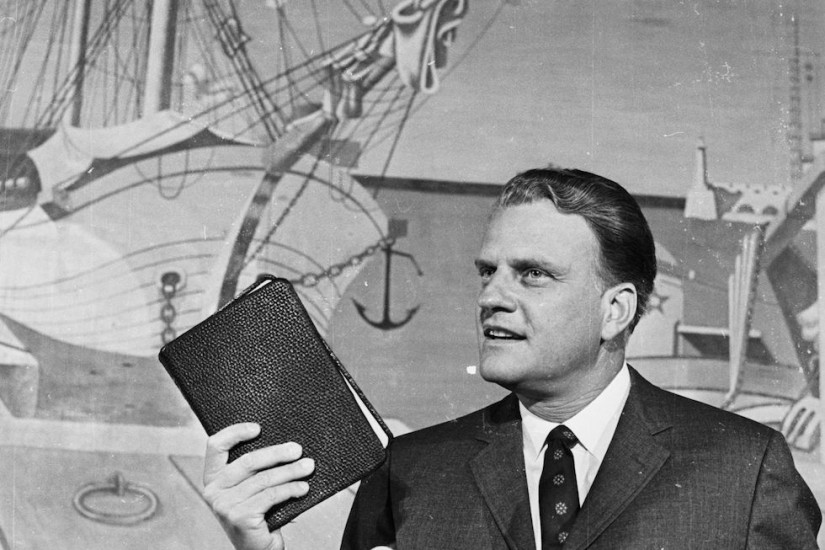

Billy Graham, who died Wednesday at the age of 99, may have been “America’s Pastor,” but he was also a man of the world. From the early days of his ministry, when he visited U.S. military forces in Korea, to his quiet message of healing at Washington Cathedral in the aftermath of September 11, Graham was a frequent commentator on—and participant in—global politics. He used his status as the most important American religious figure of the 20th century to help lead American evangelicals into a more robust engagement with the rest of the world. He was also an institution builder who was deeply invested in Christianity as a global faith.

There were other people who taught more missionaries, and some who reached more people on television; there were even those whose preaching events rivaled Graham’s in size. But no one else did as much to turn evangelicalism into an international movement that could stand alongside—and ultimately challenge—both the Vatican and the liberal World Council of Churches for the mantle of global Christian leadership.

In Graham’s early days, he was known as both a straightforward anti-communist and a crusader for souls. “Either Communism must die, or Christianity must die,” he famously said, “because it is actually a battle between Christ and the anti-Christ.” When the Billy Graham Evangelistic Association organized the World Congress on Evangelism in 1966, they chose to hold it in the divided city of Berlin, which Graham called a “symbol of freedom and democracy.” For Graham and his people, the Cold War and the expansion of American-style evangelicalism were two sides of the same coin. This was a vision that held sway among American evangelicals for the next two decades, although it would also soon be challenged by the very globalization of the church that Graham sought to champion.

Eight years later, Graham’s organization helmed an even larger and more important Congress in Lausanne, Switzerland. That event brought together 4,700 evangelicals from around the world. The very choice of Lausanne, located just 30 miles from the World Council of Churches headquarters in Geneva, was symbolic muscle-flexing for the global evangelical movement. Graham had made the point plain: “There is a vacuum developing in the world church. Radical theology has had its heyday.” Evangelicals believed it was their moment.

Graham also understood, and celebrated, the fact that the future of the evangelical movement lay with leaders in the Global South. By now, Graham and others recognized that Americans, however wealthy and however large their numbers, were not the future of the global evangelical movement. He saw that demographics were moving all of Christianity, but particularly evangelical and charismatic Protestantism, toward its future as a “third-world” religion.