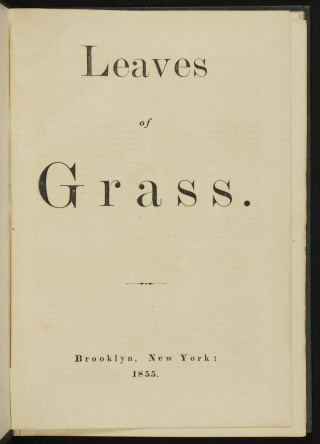

This summer is a special season of celebration for American literature. Starting in June, there will be bicentennial exhibitions, conferences, and excursions—at the Library of Congress and at NYU, respectively—to recognize the lives, work, and influence of Walt Whitman and Herman Melville. But the bicentennial of a third important American writer will not be so honored. The oldest of the trio by four days, Julia Ward Howe was born in New York City on this day, May 27, in 1819.

Including Howe in this bicentennial list may startle readers unaccustomed to thinking of her as a major literary figure. Although she wrote the words to “The Battle Hymn of the Republic,” words that are better known around the world than anything by Whitman or Melville, Howe has moved to the margins of literary history. Out of her three volumes of poetry, the “Battle Hymn” is the only lyric that has outlived its author. But Howe was famous for much more than her writing. After the Civil War, she assessed and abandoned her poetic ambitions to become a leader of the women’s suffrage movement, an advocate for world peace, and a tireless worker for human rights. By the time she died, in 1910, she was far more famous in the US and internationally, and more widely and publicly mourned, than either of the two men.

Whitman and Melville were profound and original writers who revolutionized American literature. But the difference between their careers and critical reputations and Howe’s is about gender as well as genius. As the literary historian Paula Bernat Bennett noted, “no group of writers in United States literary history has been subject to more consistent denigration than nineteenth-century women, especially the poets… Their writing has been damned out of hand for its conventionality, its simplistic Christianity, its addiction to morbidity, and its excessive reliance on tears.”

In fact, Howe’s poetry was neither pious, sentimental, nor morbid. She attempted to challenge expectations of women’s writing, addressing some of the very same controversial issues of language and sexuality that Whitman and Melville took on. But she was silenced by the demands of a dictatorial husband and the gendered conventions of the literary marketplace. It’s no accident that the most daringly original and critically acclaimed American woman poet of the nineteenth century, Emily Dickinson, was unmarried, did not have to ask permission to write, and avoided critical pressures by publishing only seven poems during her lifetime.