Kathleen Belew’s Bring the War Home and Kyle Burke’s Revolutionaries for the Right are complementary accounts of the white power movement, with Belew concentrating on white power at home, and Burke on anti-communist co-ordination abroad. Together, they show how the American movement was nurtured by its foreign experiences and how the global anti-communist movement made use of its services. Almost all white supremacists are anti-communist, though far from all American anti-communists were white supremacists.? Yet between them, Belew and Burke have illuminated a set of elective affinities between the partisans of white power and the heirs of free-market anti-communism – affinities that continue to produce explosive results.

The Vietnam War fused white power and anti-communism together. Shared wartime experience during World War Two seems to have reduced racism in the ranks – Truman went on to desegregate the military in 1948 – but Vietnam did the opposite. For the first time in any American war, black troops were over-represented in the ranks. Their presence became a galvanising political issue for the civil rights movement, whose activities in turn became a political issue for many serving white soldiers, who came to view black soldiers as unreliable or worse. As US forces evacuated Saigon, the more conservative among them felt that they had lost one war only to return home to lose another: the civil rights movement had put black rights on the national agenda in a way that imperilled the white future. Riots broke out on bases and aboard ships. At Cam Ranh Bay naval base, black servicemen revolted when white soldiers celebrated the death of Martin Luther King by raising the Confederate flag. The US military leadership fumblingly tried to accommodate the growing number of Black Power activists in Vietnam – military bureaucrats started investigating commanders who did not allow black troops to wear Afros and slave bracelets – but many troops returned from the war committed to a struggle between races.

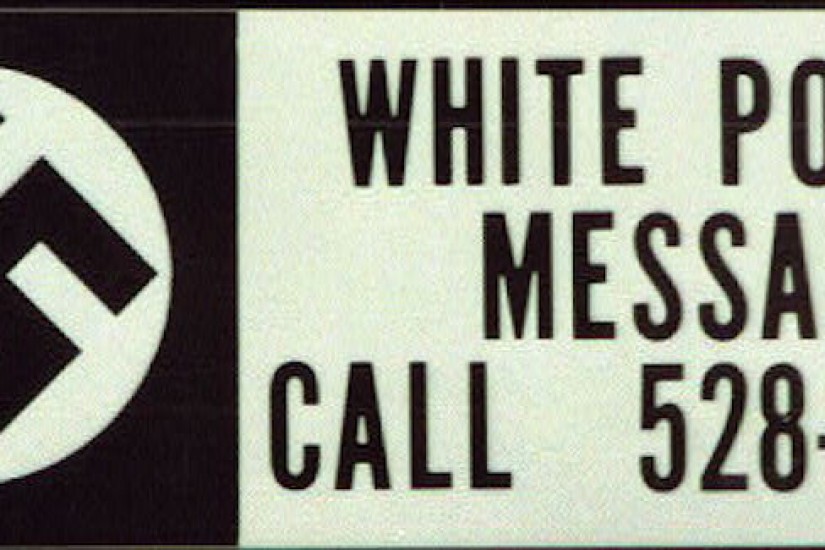

The Vietnam War had a further pernicious effect: it helped make possible the paramilitary expression of racist sentiment. In the first half of the 20th century the American far right had conducted a campaign of violence against blacks and others, especially in the South. But while they could rely on the support of large sections of society for their cause, their main aim was to instil fear rather than to try to realise fantasies of extermination or separatism. The capacity for more directed violence among white power groups that became evident in the 1980s would not have been possible without their Vietnam training and access to weapons stolen from military bases. Faced with an economic recession exacerbated by the war’s vast expenditures, many veterans believed they would never find ordinary employment, which led some to gravitate toward the fringes of American society both left and right.