Ghana’s independence from Britain on March 6, 1957 signaled a sea change. Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr. traveled to Ghana to attend its independence ceremony and marveled at the revolutionary optimism. “This event,” he said, “will give impetus to oppressed peoples all over the world…segregation in America and colonialism in Africa are based on the same thing—white supremacy and contempt for life.”[1] The spirit of a Pan-African and internationalized struggle continued at the All-African People’s Conference in December of 1958, where hundreds of delegates met in the Ghanaian capital of Accra. Ghana’s prime minister, Kwame Nkrumah, and rising star Patrice Lumumba, the leader of the Congolese National Movement, spoke stirringly on their continent’s bright future. With good reason, many believed something better was possible.

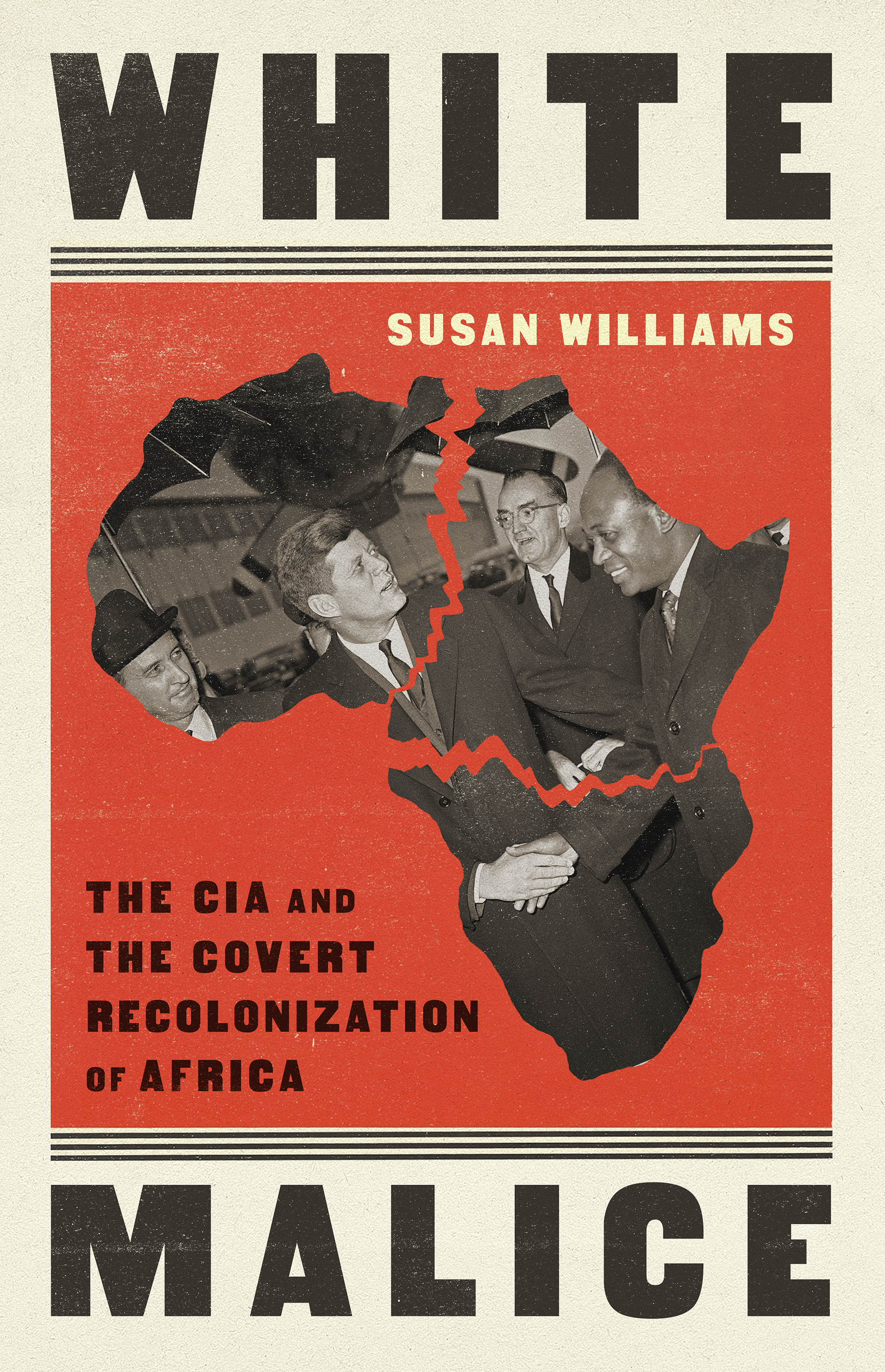

U.S. intelligence agencies wasted no time subverting surging African nationalism, as British historian Susan Williams painstakingly details in White Malice: The CIA and the Covert Recolonization of Africa. Williams draws extensively from archival research and declassified documents to show how the CIA, operating on behalf of myriad geopolitical and financial interests, deposed a generation of idealistic African leaders. White Malice is structured around the stories of Nkrumah, Lumumba, and their respective nations, which offer demonstrative case studies of the CIA’s malign presence. By early 1961, Lumumba had been exiled and assassinated, barely six months after he had been democratically elected as the Republic of the Congo’s first prime minister; and Nkrumah faced ongoing campaigns to destabilize both his government and the larger Pan-African project.

The U.S. attempted to distance itself from the old European colonial regimes—at least rhetorically—as it engaged with the postwar Third World. Appealing to its own national mythology, it emphasized its commitment to the spread of freedom. However, the U.S. had also taken responsibility for the global capitalist system and was preoccupied with ensuring that “freedom” was sympathetic to its interests abroad. The Soviet Union simultaneously offered an alternative path to modernity that Odd Arne Westad suggests allowed “poor and downtrodden peoples [to] challenge their conditions without replicating the American model.”[2] From the perspective of U.S. policymakers, independence in the Third World was dangerous. Newly independent nations could move towards the wrong form of modernity if not properly guided. Intervention, particularly in the form of covert action, became a fast-track corrective for unsavory political developments. William Casey, former Director of Central Intelligence, confirmed that the Cold War’s “primary battlefield” was “not on the missile test range or the arms control negotiating table, but in the countryside of the Third World.”[3]