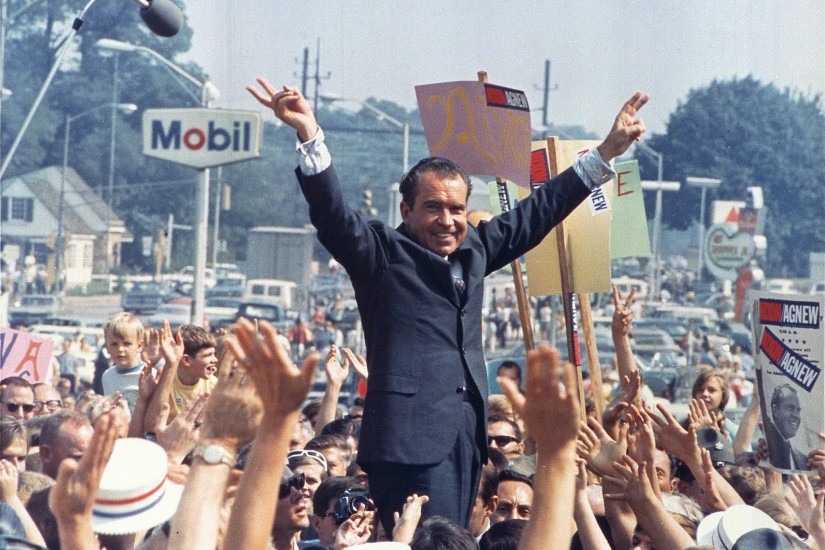

Today when politicians talk about reforming SNAP, Medicaid, or Medicare, we can be pretty certain they mean reducing benefits. But almost 50 years ago, politicians proposed, and sometimes won, social benefit reforms that actually made aid programs more comprehensive. And, as Richard P. Nathan explains, one important agent of this effort was none other than Richard Nixon.

Nixon was a well-known opponent of the expansion of federal benefits under Lyndon B. Johnson’s Great Society program. Years after he left office, his domestic policy chief recalled that Nixon thought the programs wouldn’t be able to fulfill their promise with African-Americans because he believed they were inherently less intelligent than whites.

Like his Republican counterparts today, Nixon framed his ideas about reform in terms of getting people to work and giving states flexibility. But, Nathan writes, he only called for greater local control over things like education, workforce training, direct social services, and law enforcement. Nixon believed transfers of cash and in-kind services were federal responsibilities, modeling them after Social Security.

According to Nathan, Nixon’s most ambitious effort was the Family Assistance Plan, a precursor of the concept of universal basic income, which promised to replace unpopular welfare and social services with a simple cash payment. He presented the idea as an extension of decentralization, allowing individual recipients to choose how to spend the money rather than providing services through a bureaucracy.

“The best judge of each family’s priorities is that family itself,” Nixon said.

Nixon also proposed requiring employers to offer health insurance, and transforming Medicaid from a federal-state collaboration to a fully federal program. Discussing his health care proposals, the president cited the precedents of the minimum wage, disability, and retirement benefits, and occupational safety and health standards. “Now we should go one step further and guarantee that all workers will receive adequate health insurance protection,” he said.

While many of the president’s proposals foundered, he did end up expanding the welfare state. Over the six years Nixon held office, Nathan writes, total domestic spending rose from 10.3 percent of the gross national product to 13.7 percent.

Why did a Republican president run domestic affairs this way? In part, it was a sign of the times. The New Deal consensus that heavy-handed government were basically necessary for the economy hadn’t yet broken down, and many people from both parties assumed that social programs would continue to grow.

After all, Nathan writes, Nixon’s health plan was a response to a single-payer, tax-funded plan offered by Senator Ted Kennedy. And when the president established an Urban Affairs Council immediately after his election he “charged his advisors to develop a bold program so that in later years people could not accuse them of being too cautious.”