In 1943, at Dugway Proving Ground, southwest of Salt Lake City, the U.S. Army built a Japanese village with rows of Japanese-styled homes, furnished with tatami mats and paper screens—targets to test bombs, alongside a German counterpart nearby. The goal was to understand which weapons burned the homes quickest and most effectively.

Two years later, on March 10, 1945, U.S. B-29 bombers raced above Tokyo. The pilots flew low, between 5,000 and 9,000 feet, dropping 1,665 tons of incendiary bombs on tightly packed wooden houses in the city’s eastern lowlands—areas selected for their high flammability and population density. A rancid smell crept into the planes, and a cloud of smoke covered the city, obscuring an estimated 100,000 people killed and nearly 16 square miles burned to the ground below. In June 1947, as U.S. forces assessed the damage on the ground, the United States Strategic Bombing Survey concluded that this was “[b]y far the most effective air attack against any Japanese city.” And, as the first low-flying U.S. raid of the war, it “resulted in a greater degree of death and destruction than that produced by any other single mission in any theater during World War II.”

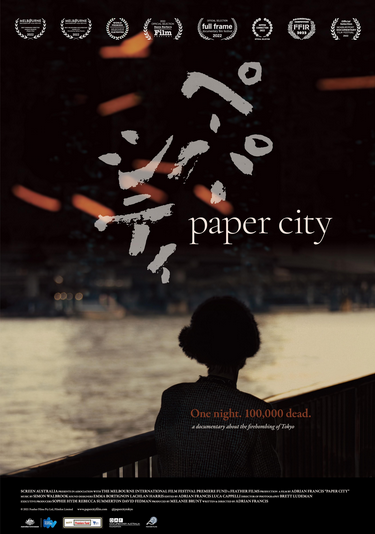

Nearly 80 years later, there is still no large American outpouring of grief or criticism or moral reckoning with the destruction of Tokyo. The leveling of Dresden by U.S. and British bombs in February 1945, one month prior to the raid on Tokyo, is inseparable from controversy, with the Encyclopedia Britannica entry on the attack noting that it is “one of the most controversial Allied actions of the war.” And the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki—sources of continued and bitter discourse within American society—are debated with great intensity on a near-fixed yearly calendar. But the March 10 raid, and the mass bombings carried out on other Japanese cities, is often heroic, necessary, successful, or outright absent from American memory, with discourse muffled and subdued.

Most books or films mentioning March 10 entangles the attack in the American myth of “the good war”—what Elizabeth Samet recently called a “versatile, durable myth.” Take Malcolm Gladwell’s The Bomber Mafia, a popular and recent example. Here, the raid is the climax to a heroic and daring epic of American military men, grappling with the responsibilities and perils of air power. He portrays that night through the eyes of American pilots and officers, with stories of bombs falling and Gen. Curtis LeMay puffing his cigar, anxiously waiting for his pilots to return. The civilian deaths below are tragic but necessary and given a few sentences: nameless mothers with babies burning in the night; collateral damage, forgotten, ignored.