Artillery lit up the predawn skies above Charleston, South Carolina, on April 12, 1861, heralding the beginning of four long years of the American Civil War. The Union’s standing army numbered fewer than 20,000 troops, most of whom were stationed along the Canadian border or on the western frontier. They needed recruits.

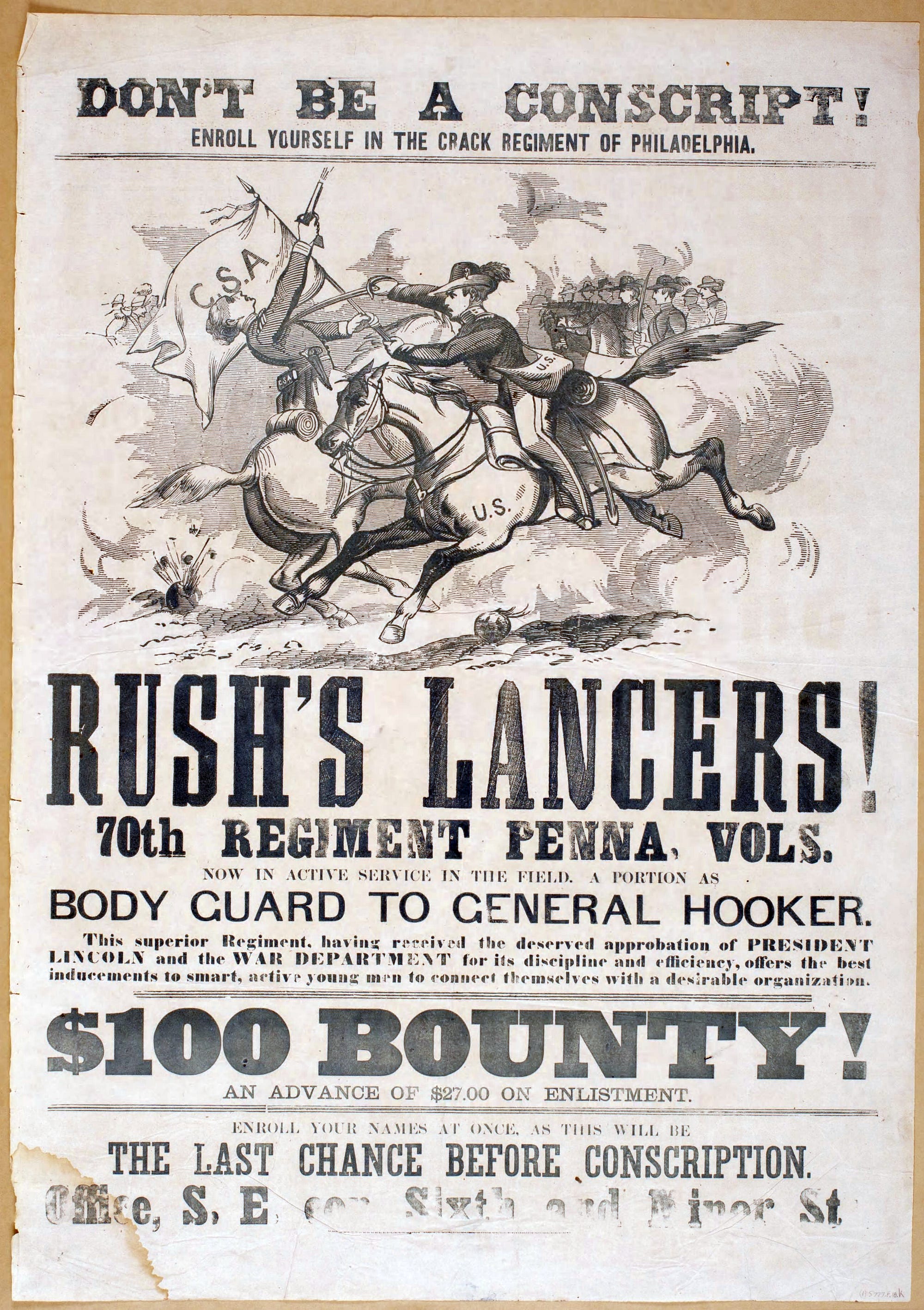

In Northern cities, presses fired up to print recruitment broadsheets. Illustrators decorated posters with patriotic imagery, appealing to hearts as much as passing eyes. The eagle, which represented American unity since the waning days of the Revolution, was a favorite icon. Stars and stripes flowed freely across the pages of newspapers, a reminder of the republic that was being torn apart. Uncle Sam was at the time an amorphous cartoon who would find resolute form only during World War I, but imagery of the instantly recognizable founding father, George Washington, helped inspire the masses. Artists also relied on universal characters such as Lady Liberty and Justice. Slogans were about honor, duty, glory, valor, and the constitutional ideals of a democratic, united nation.

Civil War-era envelope. (The Library Company of Philadelphia)

But recruitment posters ignored the key moral underpinning of the entire war. Absent from recruitment drives is any mention of slavery. Sneering caricatures of Johnny Rebel appealed to Northerners’ sense of outrage, but they did not depict the plight of millions of blacks trapped in the newly formed Confederacy. Abolition was a contentious issue, and the government was wary of further weakening the Union’s tenuous harmony, so military posters promised signing bonuses and warned about an impending draft. The tensions about race and class would erupt in the summer of 1863, when rioting conscripts killed more than 100 African Americans in Manhattan.

Private enterprise, on the other hand, gleefully seized upon the issue of slavery. Stationery companies produced envelopes adorned with art and slogans reflecting the divisive politics of the day….

The era of 24/7 news feeds beaming battle footage halfway across the world was more than a century away, and photography was in its infancy. But as the mechanizations of war ground soldiers to bloody bits, the gory reality of the front lines was brought to life by illustrators and set by lithographers working on behalf of the Fourth Estate. Finally, the rest of America could see that regiments of black Union soldiers were living and dying alongside their white countrymen.