No other country protects controversial speakers with the zeal of American First Amendment doctrine. Whether American free speech exceptionalism is a good thing remains deeply contested, and the Charlottesville events of Aug. 11 and 12 show why.

America’s hard-line approach to free speech takes many forms. Public officials and public figures, for example, must clear a daunting array of First Amendment hurdles before they can win a libel suit against their critics, even when what is said about them is plainly false. Other countries disagree, and believe the United States sacrifices too much of the value of reputation on the altar of free speech—just as American free speech enthusiasts believe that the approach elsewhere leaves too little breathing room for harsh criticism of those who make and influence public policy.

Similarly, the United States protects free speech and free press against the claims of privacy more vigorously than do other countries, and it is more permissive of publishing unlawfully obtained information (as with the Pentagon Papers in 1971). More relevant to recent events, the United States, as a result of Supreme Court rulings going back to the 1960s, erects a high bar before it will punish those who advocate or incite illegal action; the advocacy must be explicit, and the incitement must produce an actual likelihood of imminent illegality. Short of explicit and immediate encouragement of an angry mob, the United States—alone among nations—tolerates almost all advocacy, even advocacy of unlawful violence.

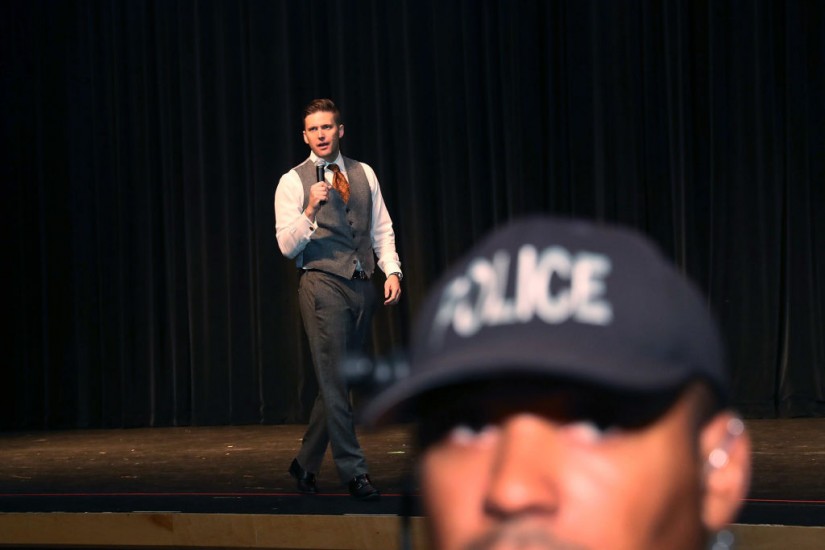

Where the United States departs most dramatically from the approaches elsewhere is with what is commonly called “hate speech”—speech that incites or encourages race-based violence or discrimination, or denigrates people because of their race, religion, ethnicity, sexual orientation or gender. Even though many people in Charlottesville and at the University believed, correctly, that the Klan, the neo-Nazis and other white supremacist groups engaged in hate speech, many people also believed, incorrectly, that the offenders had violated the law in doing so. That conclusion would be correct for much of the world—where authorities prohibit incitement to racial hatred, Holocaust denial and other forms of hate speech—but not in the United States. Supreme Court decisions dating, again, to the 1960s have made clear that not only does the Constitution not recognize the category of hate speech, but it also plainly prohibits targeting speakers because their message is racially hateful, hurtful or outrageous.