Q: You said the goal of your book project is to try to distinguish antimonopoly from antitrust. Can you explain?

The idea is to try to explain to contemporary Americans why so many of their predecessors found economic concentration so troubling, and what’s happened to that tradition. I think that antitrust is a much more limited dimension of antimonopoly than you would assume if you were looking at the historical literature, but it’s come to be identified with it.

Q: Can you explain what you see as the difference between the two? Why are they not synonymous?

We’ve got this tradition called antitrust, which became the platform for the development of this increasingly arcane body of law that solves a practical problem for businesses: what kind of conduct is legal, what kind of conduct is illegal? And that led to this elaboration of antitrust doctrine through the 20th century that exfoliated and developed all kinds of permutations that eventually collapsed intellectually in the 80s following the publication of anti-antitrust screeds such as Robert Bork’s 1978 Antirust Paradox.

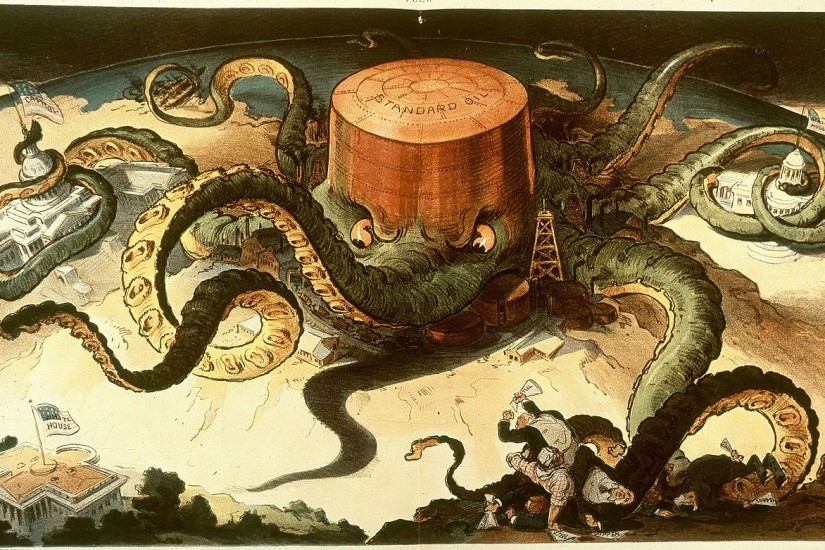

If you conflate antimonopoly with antitrust, it’s a story of the late 19th century, with some successes in the early and mid 20th century and then collapse. So you’ve already left half of American history out. The tradition is much more important than that, and has much wider roots. We often don’t remember that the Boston Tea Party had an antimonopoly dimension. So too did Andrew Jackson’s protest against the Bank of the United States. The great concern among 19th century Americans was political power, concentrated political power. And that concern was not with economic performance, but with power, and the ways in which economic concentration can manipulate the political order.

Q: In your 2012 paper Robber Barons Redux: Antimonopoly Reconsidered, you explain that business historians such as Alfred J. Chandler Jr., whom you studied under during your PhD in Harvard, largely abandoned the critical examination of 19th century monopolists, the so-called “robber barons,” and started treating them as industrial statesmen and “organization builders” who became the beneficiaries of certain institutional arrangements, instead of critically examining the political economy in which they’ve come to dominate. Why did this shift occur?

Late-19th century business leaders were reviled. They got very little good press outside of the press that they had paid for. That doesn’t change until the First World War, when corporate public relations is invented, in large part to rebut these savage attacks on business. And the possibility of government ownership of the Bell System is right at the center of that epochal transformation—which, among other achievements, legitimated managerial capitalism as a business ideology. Bell managers invented corporate public relations to help ensure that they got good press, and they succeeded.