Most Americans today likely think of the Ku Klux Klan as an organization whose heyday came in the civil-rights era of the 1950s and 1960s, and of its members as lower-class white Southern men—ones who concealed their identities while waving the Confederate flag at pro-segregation rallies, burning crosses on the lawns of their enemies, or brutalizing their innocent victims. Others are perhaps familiar with the Klan of the 1860s and 1870s, which was a white and distinctively Southern terrorist organization composed of men who tortured and murdered people under cover of darkness in an effort to undermine the political and economic freedoms accorded to formerly enslaved people during Reconstruction.

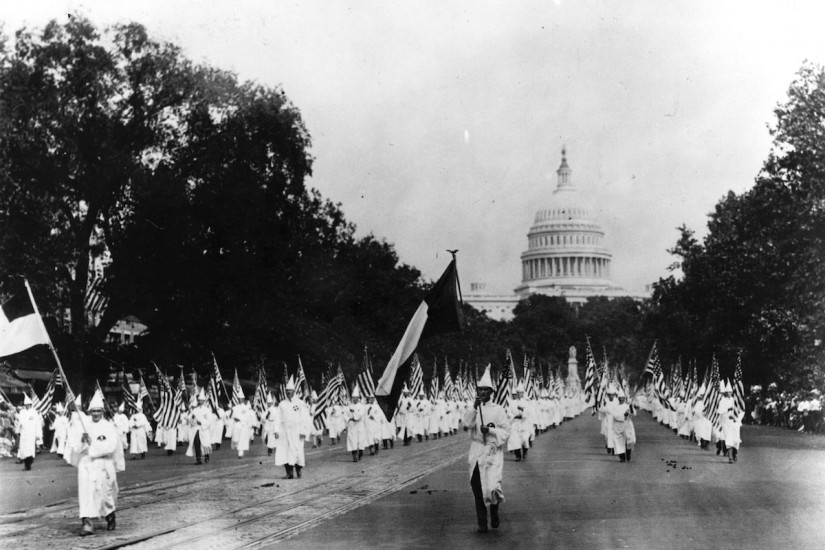

But the Klan was easily at its most popular in the United States during the 1920s, when its reach was nationwide, its members disproportionately middle class, and many of its very visible public activities geared toward festivities, pageants, and social gatherings. In some ways, it was this superficially innocuous Klan that was the most insidious of them all. Packaging its noxious ideology as traditional small-town values and wholesome fun, the Klan of the 1920s encouraged native-born white Americans to believe that bigotry, intimidation, harassment, and extralegal violence were all perfectly compatible with, if not central to, patriotic respectability.

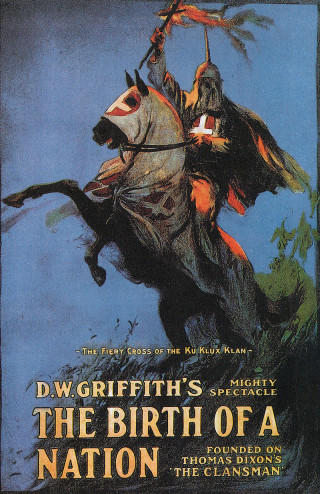

The Ku Klux Klan had been defunct for nearly a half-century when William J. Simmons decided to revive the organization in the fall of 1915. A resident of Atlanta, Simmons worked for a fraternal benefit society called the Woodmen of the World, and he already belonged to more than a dozen clubs and churches. But he had dreamed for years about founding a fraternal order himself someday, and with D.W. Griffith’s cinematic paean to the Klan, The Birth of a Nation, scheduled to debut in Atlanta, the inspiration and the timing seemed right. On Thanksgiving night, after riding with about 15 other men in a rented tour bus to a large granite formation outside of the city known as Stone Mountain, Simmons lit a wooden cross aflame and announced the rebirth of the Knights of the Ku Klux Klan.

Advertised by Simmons in Atlanta newspapers as “The World’s Greatest Secret, Social, Patriotic, Fraternal, Beneficiary Order” and a “High Class Order for Men of Intelligence and Character,” the new Klan floundered for several years. It had attracted just a few thousand members by the spring of 1920, when Simmons hired Mary Elizabeth Tyler and Edward Young Clarke as publicity agents and promoters for the group. Tyler and Clarke divided the entire country into what amounted to sales territories and sent more than 1,000 solicitors into the field to recruit members whose $10 membership fee for the Klan went in part to the solicitors as commission.