Smalls founded the South Carolina Republican Party in 1867 and, in 1868, joined 71 Black delegates to the state convention that ratified the Fourteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. In that same convention, Smalls and his fellow Black delegates adopted a progressive state constitution, providing for public education, abolishing race and property ownership as conditions for holding public office, and overturning Black Codes. He would live long enough to see his achievement dismantled in 1895, when whites regained power in South Carolina and adopted a Jim Crow Constitution. As one state newspaper put it at the time, “We can trust white men to do right by the inferior race, but we cannot trust the inferior race with power over the white man.” With some amendments, that constitution remains in effect to this day.

In the years in between, Smalls was first a state representative, then a state senator, and finally, between 1875 and 1887, a U.S. representative. He served in Congress alongside Richard Cain, the pastor of Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church, where, in 2015, Dylann Roof murdered nine Black congregants. He represented the 7th congressional district, then the 5th district; once white Southern Democrats regained power, Smalls was the last Republican to represent the 5th for nearly 130 years, until 2011, when Mick Mulvaney, Donald Trump’s former chief of staff, won the seat as part of the Tea Party wave that rose in opposition to the election of the first Black president.

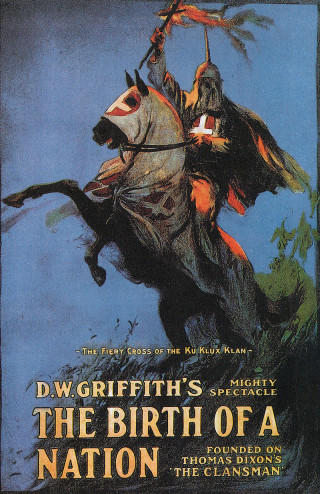

But it was while serving in the South Carolina legislature that Smalls first crossed paths, unbeknownst to him, with Tomas Dixon Jr. The latter was just eight years old when his uncle took him to observe the proceedings of the statehouse. Dixon would go on to author The Leopard’s Spots: A Romance of the White Man’s Burden, The Clansman: An Historical Romance of the Ku Klux Klan, and The Traitor: A Story of the Rise and Fall of the Invisible Empire. Dixon claimed that the memory of “ninety-four Negroes, seven native scalawags and twenty-three white men” debating affairs of state moved him to set the record straight on Reconstruction with his white supremacist trilogy.

Griffith’s movie, which drew heavily from The Clansman, opened on February 8, 1915; Smalls died two weeks later; it’s unlikely he ever saw it. The movie proved popular in part because Dixon enlisted the help of a powerful friend to promote it: President Woodrow Wilson, whom he’d met at John Hopkins University. Wilson screened the film in the White House and helped arrange a viewing for members of Congress and Supreme Court justices. When Black people urged a boycott of the film over its portrayal of newly freedmen as bloodthirsty savages, newspapers reported that the president himself had seen and liked the film.