Much of the research that has been done to create this book is invaluable. Schulman has structured the volume around 188 interviews with surviving members of the New York City chapter of the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power, better known as ACT UP. She and documentarian Jim Hubbard conducted these interviews between 2001 and 2018 as part of the ACT UP Oral History project they spearheaded. When we study the history of movements, we often look to the most spectacular moments of protest or conflict as hinge points, but smaller forms of action and organizing, often inspired by the major actions but irreducible to them, are just as important. Schulman at times recognizes this, focusing on crucial aspects of ACT UP’s ongoing legacy, like its needle exchange program or its activist-led medical research—initiatives a less capacious interview process might have easily missed. In an equally important move, Schulman and Hubbard have made the full transcripts of those interviews free and available to the public online. The value of this incredible feat of activist archivism—especially for an organization that included so many members who died young—cannot be overstated.

But the importance of that oral history project cannot overcome the intrinsic weaknesses of that archive. The survivors tell the tale, and—as Schulman points out throughout the book, survival in the AIDS crisis was heavily skewed towards cis white gay men with access to legal, media, financial, and scientific resources. Therefore any record given mostly by activists who survived into the 2000s will overrepresent those men, especially in an organization where they already made up a disproportionate percentage of the activist base. And memory is also unreliable, as we continue to learn and grow, and certain attitudes, analyses, and experiences calcify into particular, often self-flattering narratives.

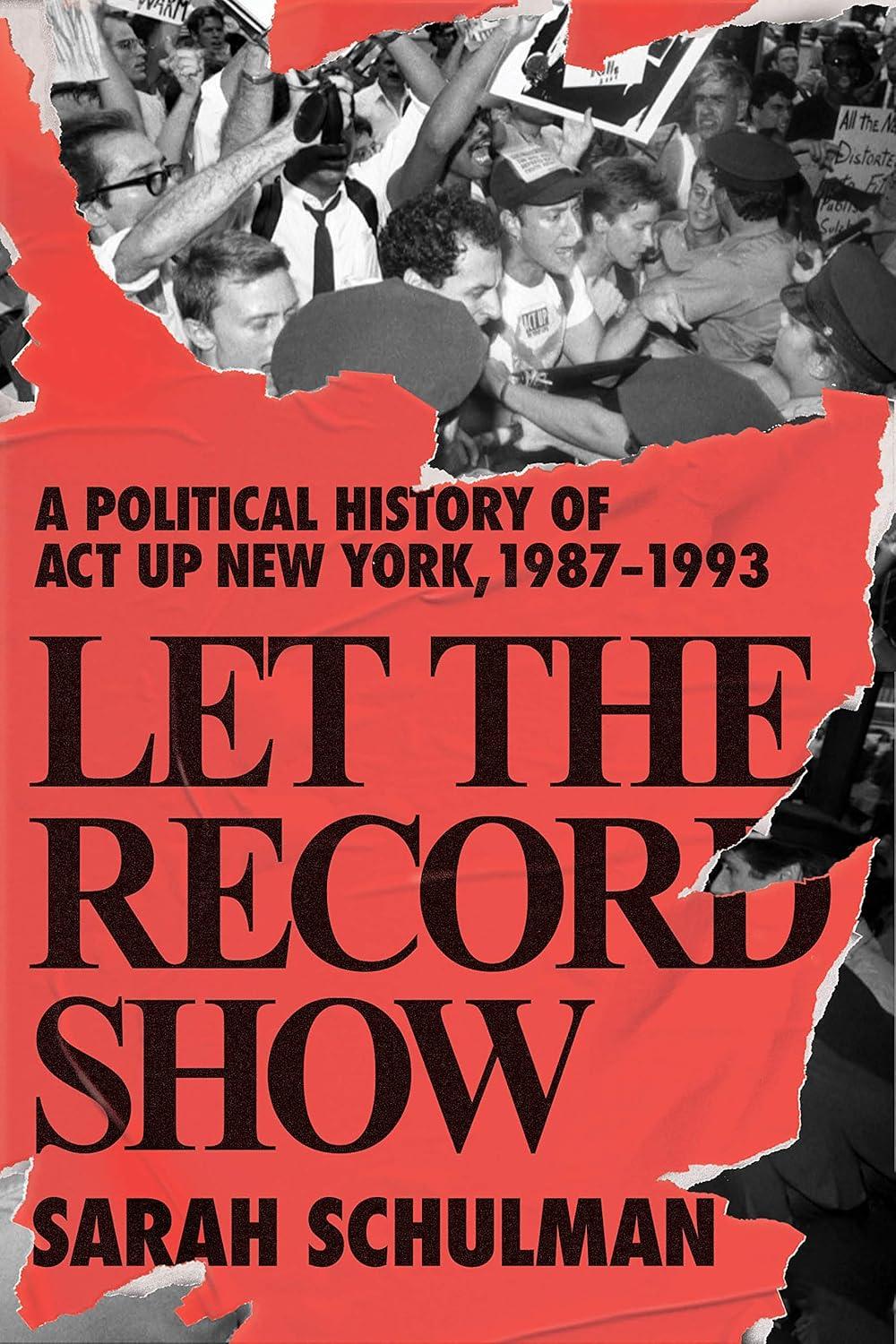

Thus the importance of supplementing the post-movement accounts of participants, especially those given decades later, with other kinds of historical evidence: more immediate records, propaganda, and writing produced by participants, journalists, and government researchers, as well as secondary sources produced by academics or historians who employ different analytic modes. The other major well of information in the book, however, is Schulman herself: memories from her own participation in ACT UP NYC, as well as her own research and journalism. This rather vague and narrow lens allows Schulman to dismiss controversies around gender, race, and strategy that have arisen in the years since ACT UP’s heyday, even as she claims that her more immediate and personal account of the movement should serve as a corrective to others. Her preface catalogues some of the ways she sees AIDS as having been “grossly misrepresented and mis-historicized,” from the New York Times’ infamous underreporting of the epidemic to the 2012 ACT UP documentary How to Survive a Plague’s “heroic white male individual model” for understanding AIDS activism. Even the book’s title, Let The Record Show, positions her book as a quasi-legalistic account of the real truth.