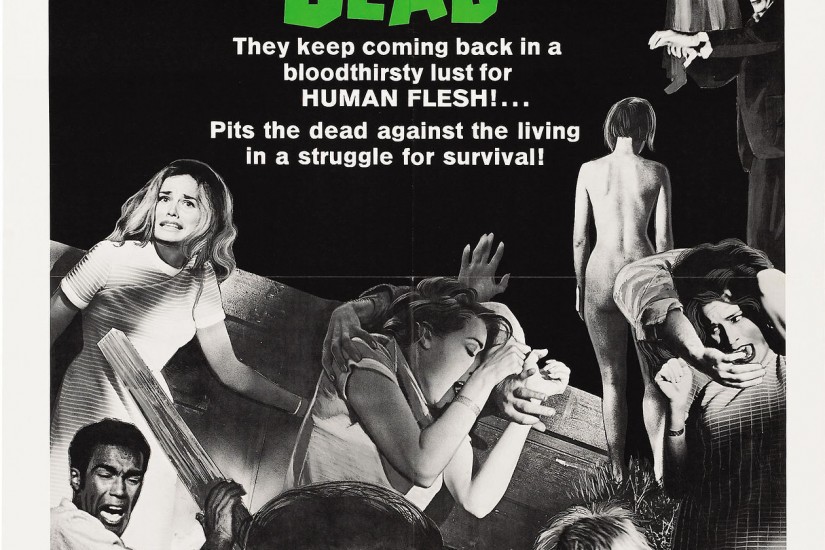

As the marauding ghouls provide a grimly hilarious cross-section of ordinary Americans, so Night of the Living Dead offered the most literal possible image of the nation devouring itself, as it brought the Vietnam War home, importing the destructive violence of Watts, Newark, and Detroit to bucolic Middle America. Not for nothing is one dazed character, traumatized by the attack of a cannibal ghoul in an American flag-bedecked cemetery, forever mumbling, “What’s happening?” It was the question of the hour.

Where Wild in the Streets was a rogue Hollywood production, Night of the Living Dead was a triumph for low-budget, regional, independent filmmaking. A piecemeal production, made with pooled savings, shot in black-and-white on weekends and between jobs, that ultimately took the better part of a year to complete, it demonstrated the power of outré independent films to provide new social metaphors and outgroup fantasies. Produced off-Hollywood, Night of the Living Dead was not bound by Hollywood conventions. The movie’s rough-hewn style had the raw immediacy of underground movies and direct documentary; its cheap but vivid effects gave Weekend’s burning cars and hippie cannibalism a vérité spin. The narrative offered no happy ending, no authoritative voice-over, no reassurance whatsoever. On the contrary, the film systematically undermines the authority of the father, the police, and the media.

Unrelentingly grim and profoundly skeptical, Night of the Living Dead is the very opposite of what Jacques Ellul called “sociological propaganda.” The besieged characters are entranced by the TV, they follow its directions explicitly, move close to it for comfort, and rejoice when it is repaired despite the fact that the TV is blatantly another world—static, sterile, and populated by officious personalities. While 1950s sci-fi movies tried to reproduce the voice of authority, Night of the Living Dead satirized it with deadpan newsreaders solemnly reciting the latest bulletin: “These ghouls are eating flesh. Repeat. They are eating flesh.”

Night of the Living Dead further asserted its marginal status by casting a black actor (Duane Jones) as the film’s smartest, most capable, and sympathetic character. Thus, although race is never overtly alluded to, viewers were more or less compelled to attribute racial paranoia to certain white characters while identifying with a minority point of view.