There are many explanations for the mass amnesia about this health crisis, not least of which is the fact that it was overshadowed by the memory of World War I. But another reason is that is that people at the time were used to death—especially death from disease—in a way that we are not today.

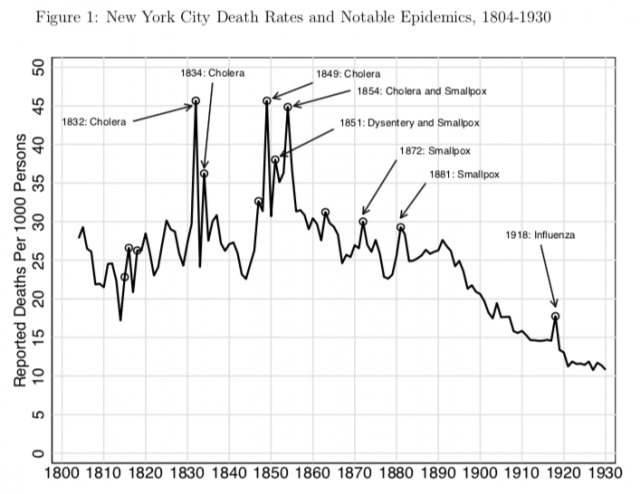

Take this graph, from a recent working paper published by the National Bureau of Economic Research:

As it makes clear, deadly epidemics were not unusual for residents in New York City, who in the nineteenth century experienced multiple cholera and smallpox outbreaks that killed more residents per capita than the 1918-19 flu epidemic. People living New York City in 1918, in other words, had gone through this sort of thing before. That same, of course, can be said about people across the rest of the country and the globe, including here in Fresno.

But it can’t be said about most of us today. We not used to infectious diseases disrupting our daily lives, destroying our economy, or killing hundreds of thousands of our fellow citizens. And this reality points to an important lesson that it is worth pondering: once the coronavirus crisis is over, it may take us quite some time to process and psychologically recover from this tragedy. It is not likely to be forgotten as easily as the 1918-19 flu outbreak.

What else can we learn from these dispatches on Fresno’s 1918-19 influenza pandemic?

Not long after I began this project six (long!) months ago, I published some preliminary lessons from the pandemic in the pages of the Fresno Bee, lessons that are worth rehearsing.**

The first lesson was that early action makes a difference. Fresno moved comparatively quickly in response to the health crisis and, as outlined above, this paid dividends.

The second lesson was that we should expect greater resistance the longer the coronavirus crisis drags on. During the first wave of the pandemic, most Fresnans seem to have followed city regulations, though some flouted the mask rule. During the second wave, however, resistance became more overt. Pool halls and other places of amusement refused to close their doors, and business owners threatened lawsuits unless they were permitted to operate unfettered. Public health officials, meanwhile, increasingly struggled to convince residents to put aside their individual interests for the good of the community.