Back in the prehistoric days of 2020 spring training, when few suspected that the pandemic would soon shutter the game and send fans into a tailspin, Major League Baseball was set to begin the season under a very different cloud. A few months earlier, not long after the 2019 World Series came to its exciting conclusion, the website The Athletic revealed that the Houston Astros had placed video cameras in their stadium to record, decipher, and track the hand signs by which opposing catchers would indicate upcoming pitches, and had then employed audible relays from the dugout to alert their batters as to what pitch to expect. Amateur fan videos from the 2017 and 2018 seasons confirmed, in vaudevillian strokes, the final workings of this bold semiotic heist, which involved the banging of metal trash cans in the Astros’ clubhouse. A league investigation resulted in team penalties, the suspension of managerial personnel, and the derailing of several coaching careers. More ominously, the sign-stealing scandal precipitated angry tirades and threats from rival players, especially members of teams the Astros had defeated in 2017 en route to a World Series victory that now seemed shrouded in disrepute, branded in the popular imagination—if not the official record books—with a scarlet asterisk.

For those outside the sport, the episode must have seemed confusing. Apparently it was kosher for catchers to send secret signals to pitchers, and standard practice (though subject to informal grievances among players) for opponents to try to intercept these signals, but scandalous for the Astros to devise their own signal system to communicate the results of their espionage. The sign-stealing scandal, in other words, raised interesting questions about rule keeping, technology, and what counts in the symbolically fraught game of baseball.

Beyond the many performers, employees, shareholders, and bettors who have material stakes in the stability of the nation’s most venerable spectator sport, intellectuals continue to be drawn to baseball as a terrain for working out the kinds of philosophical problems that the Astros’ misdeeds brought to the surface. And all current writing about baseball, academic and popular, unfurls against the backdrop of the so-called sabermetric revolution, brought to lay attention through Michael Lewis’s blockbuster book Moneyball: The Art of Winning an Unfair Game (2003) and its subsequent film adaptation (2011). Under the broad influence and banner of the Moneyball book and movie—twin odes to the ability of the Oakland Athletics to compete against wealthier teams by paying low salaries to undervalued players—fans and readers imagine that the 21st-century game has become a completely new enterprise, either because subjective and romantic assessments of baseball prowess have been supplanted by quantifiable evidence, or because crude and noisy statistics have been replaced by meaningful data.

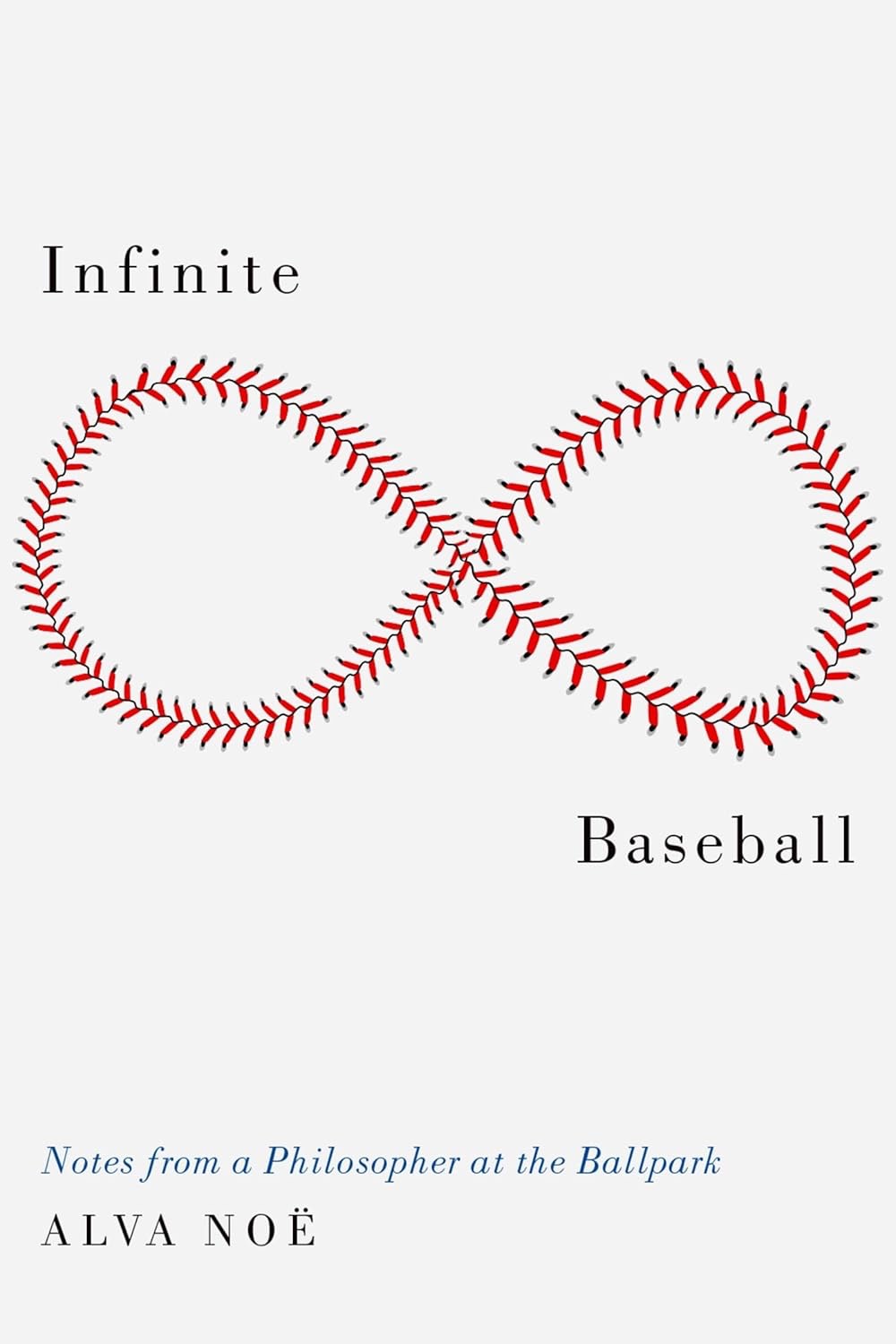

But has baseball changed, really? And do those changes have moral implications? Such questions about the character of the game were probed recently—just prior to the eruption of the Astros scandal—by three new books. Alva Noë’s Infinite Baseball: Notes from a Philosopher at the Ballpark conceives of baseball as a “forensic” sport and, in so doing, sanctions a wide range of otherwise taboo activities (doping included). Christopher Phillips’s Scouting and Scoring: How We Know What We Know about Baseball presents a provocative argument for the game’s consistency despite technological advances, and Ben Lindbergh and Travis Sawchik’s The MVP Machine: How Baseball’s New Nonconformists Are Using Data to Build Better Players, while celebrating the brave new world of gadgetry and modeling, concedes that subjective, human judgment stubbornly persists. Read together, the books challenge both avid fans and cultural critics to reconsider what they think they know about baseball.