Graduating from the University of South Carolina in 1877 with a degree signed by Governor Wade Hampton, who had served as an officer in the Confederate army and owned slaves, Cornelius Chapman Scott tried to make a decent life for himself under difficult circumstances. Scott worked in upstate South Carolina as a public school teacher and Methodist preacher, striving to help the most vulnerable members of the state’s African American community cope with the new realities. But in the spring of 1880, the well-educated, well-to-do, mixed-race Charlestonian caught a glimpse of the apocalypse.

A local theater was presenting the biblical Book of Revelation through a panorama—a high-tech, immersive, virtual reality conjured by a moving set with simultaneous narration. Hearing good reviews, Scott was eager to watch the four horsemen rampage across the palm-bedecked, subtropical landscape. On a springtime Thursday night, Scott arrived at the Greenville Opera House box office and paid his fifty cents for a ticket. Seating at the theater had long ago been desegregated, so Scott was taken aback to receive a “half-ticket” entitling him to a balcony seat and twenty-five cents in change. He insisted he wanted a “full ticket” and, after pushing his half ticket and twenty-five cents back to the clerk, he was given one.

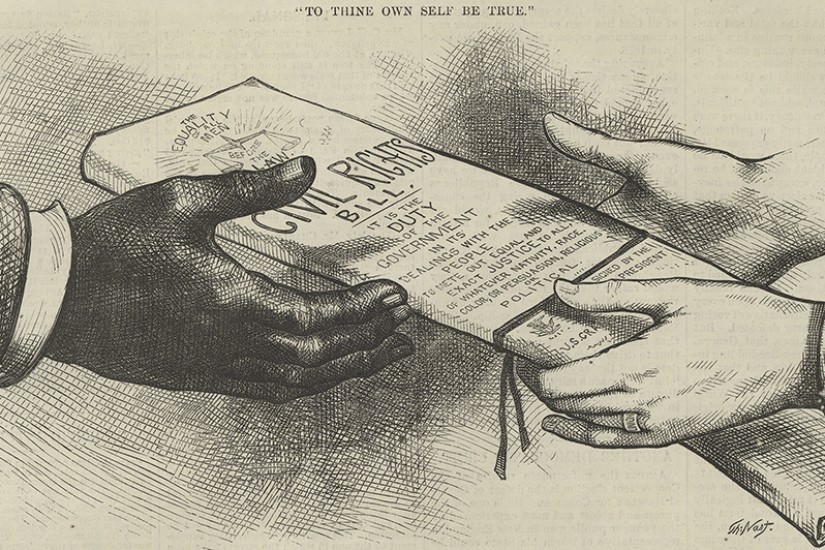

But when Scott took his assigned seat, a white man approached, pointed to the balcony, and instructed, “The gallery is for colored people.” Scott stayed put. As the music began and the panorama commenced, Scott again thought the matter resolved. But midway through the show, a policeman arrived—“a contemptible ‘poor white trash’ who look[ed] more like a colored than a white man,” as Scott later recalled—and tried to remove him by force. Scott refused to move, telling the officer that he could arrest him, but he would not comply voluntarily nor would he physically resist. Only when the policeman grabbed Scott by the shoulders did he budge. As Scott was escorted through the theater lobby, the management attempted to refund his money but, to show he was leaving against his will, Scott refused. “I was now sick of the thing,” Scott recounted soon after in a letter to his father. “I was boiling with indignation, but kept perfectly cool.” No matter how bad things were in South Carolina, Scott knew he could bring a case under the federal Civil Rights Act of 1875. Scott had done everything a civil rights plaintiff should do to win a case—not leave voluntarily, not resist the police, and not accept a refund—but when he approached an attorney, the lawyer was dubious. Trying to recover money from the policeman would be hopeless as he almost certainly had no savings, but suing the Greenville Opera House raised other problems. One of its owners was a county official. And justice was anything but blind in the now “redeemed” State of South Carolina, especially upstate.