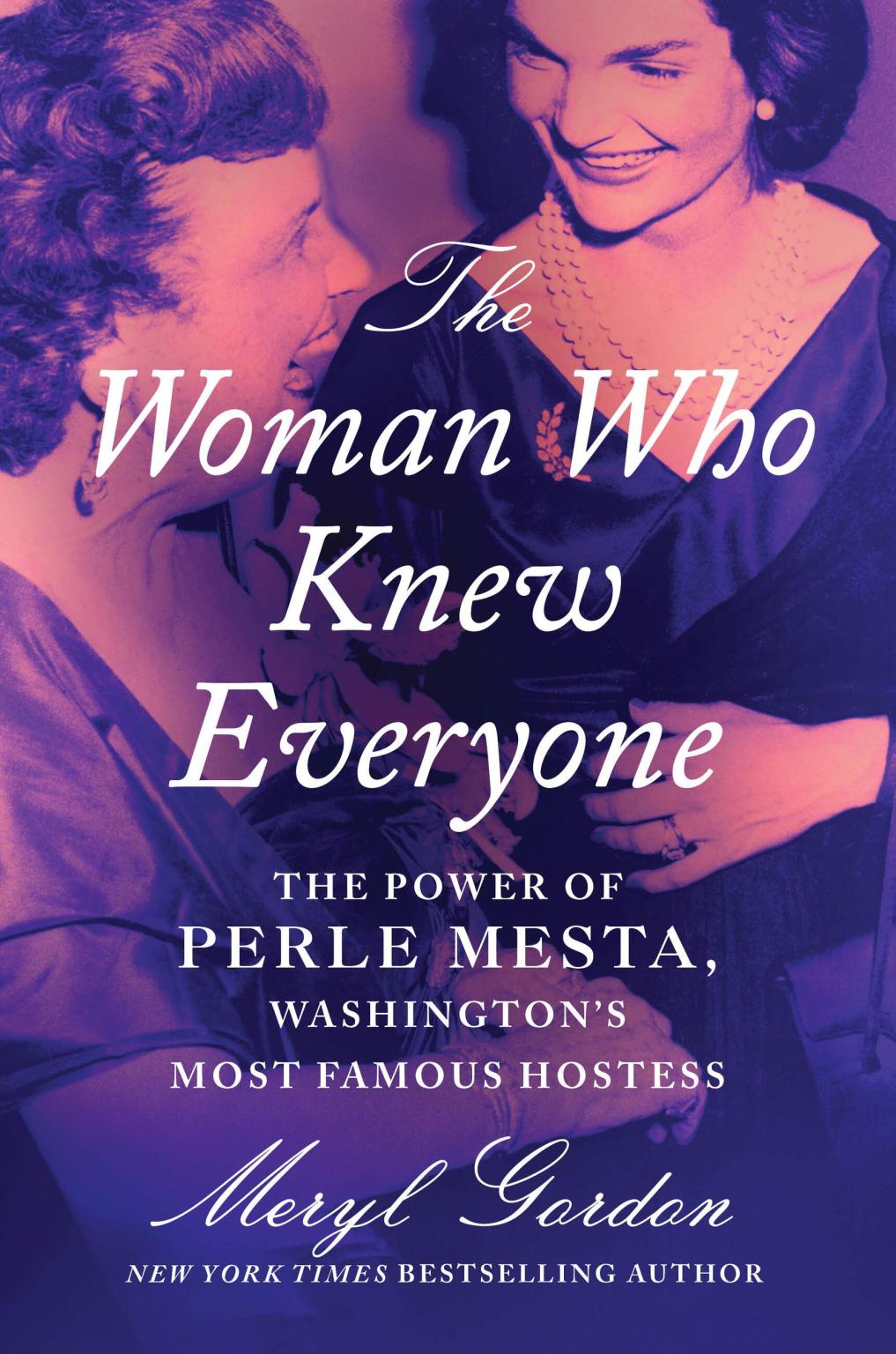

Reality aside, it is Perle Mesta, not Evalyn McLean, whose name is still remembered, albeit a bit dimly, fifty years after her death. With political loyalties that oscillated between Republicans and Democrats, Mesta was not especially interested in amassing Washington’s usual currency, power. It was notice that she wanted, and she achieved an everlasting degree of it as “the hostess with the mostes’, ” Ethel Merman’s character in Irving Berlin’s Broadway musical “Call Me Madam” (1950). Mesta didn’t run a salon; she threw soirées. As Meryl Gordon explains in her new biography, “The Woman Who Knew Everyone” (Grand Central), “Perle wanted her guests to unwind and enjoy themselves, to look forward to seeing new entertainers and surprise performers.” Sam Rayburn, the Speaker of the House, called her Perly-Whirly. She sent her guest lists to the society pages of the city’s newspapers, and then invited the reporters themselves.

Born in 1882, Pearl Skirvin—she later Frenchified her first name to Perle—grew up in Texas and Oklahoma, where her father, whom she revered, made fortunes in land speculation, oil, and construction. The Skirvin hotel still stands in Oklahoma City, and it was there, Perle said, that she got her “first interest in politics from eavesdropping on the lobby conversations.” She adopted, at least initially, her father’s Republican politics, and, more lastingly, the Christian Science beliefs of her younger sister, Marguerite, who had a successful career in silent films. Perle served as Marguerite’s chaperon for a number of years before marrying George Mesta, a rich industrialist, in 1917. The couple settled down outside Pittsburgh, in a plutocratic version of living above the store. “Her husband owned a ten-thousand-square-foot 1880s mansion on the bank of the Monongahela River. But the view from the picture windows was hardly scenic,” Gordon writes. “The Mesta Machine Company, with manufacturing buildings on twenty acres, spewed smoke and grit into the sky.”

The First World War prompted a life-changing move to Washington, when Woodrow Wilson’s Administration required consultations with George about steel production. The Mestas rented a suite at the Willard Hotel, and Perle became friends with another guest, Thomas Marshall, the Vice-President remembered for saying that what the country really needed was a good five-cent cigar. She was soon going to dinners, including some of Evalyn McLean’s, and then giving parties, small ones, of her own. Gordon explains, “She wasn’t trying to press a political agenda. But she liked being adjacent to power and useful to George by socializing with politicians.” Her husband “liked to show off his wealth,” and he gave a hundred thousand dollars to the 1924 campaign of Calvin Coolidge. Though she was less conservative than George—she frequently stuck up for his workers back in Pittsburgh—Perle wouldn’t back a Democratic ticket for another twenty years.