But it’s the third tack to understanding Whitman which actually may be the most relevant and direct lesson of Whitman’s. What Emerson called “the long foreground” of Whitman’s was mostly journalism and self-publishing. Whitman, who left school at age 11, trained as a printer’s devil. And, throughout his career, he was intimately tied (in a way that very few writers are) to the physical production of his own work. He worked as a typesetter for publications in New York, founded his own newspaper The Long Islander, and for two years was the editor of the well-known Brooklyn Eagle. What he mostly was, though, was a failure. The self-publishing didn’t earn much. His practical-minded brother George would lament that “he made nothing of his chance” during the “great boom in Brooklyn” in the 1850s. And Whitman, who seems to have been living rough as much by necessity as poetic persona, would in 1840 style himself as part of a “loafer kingdom”.

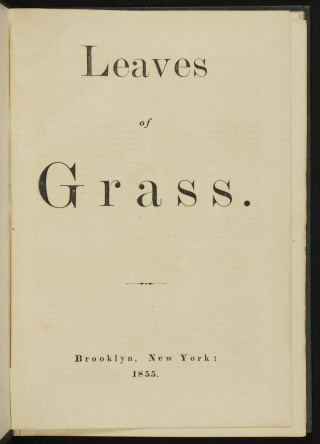

But it was Whitman’s outsiderness — combined with his willingness to take control over the means of production — that accounted for his literary miracle. High-brow American literature in Whitman’s time was awful, really awful — stale hand-me-downs of European prosody — and Whitman, too, struggled to break free of it. “I too, like all others, was born in the vesture of this false notion of literature,” he said late in life. But he did break free of it. He came across enough fresh influences — Martin Tupper, Emerson himself — that he was able to develop a more distinctively American sensibility, augmented with the language of the streets and a dash of the pulpy writing emerging from the nascent penny presses. And by 1855, he was able to take care of the publication of Leaves of Grass entirely by himself — writing parts of the famous preface directly onto the keys of the press in the print shop, and then handling his own advertising and distribution.

What Whitman was doing sounds, of course, very much like blogging or Substack — and I have no doubt that if he were alive today that’s exactly how he would be distributing his work. In an excitable mood, I wrote on my Substack recently that “what we’re really on the cusp of is a whole different way of being”, and what I meant was the capacity of the internet to eliminate gatekeepers and to open the way for the “new, superb democratic literature” that Whitman described. This statement of mine was met with some skepticism. If Emerson “rubbed his eyes a little” at Leaves of Grass, the Substacker Teddy Brown had to “close [his] eyes and rub [his] temples” at the sheer stupidity of what I was saying.