In 1966 and 1967 a group of left-wing intellectuals and radical activists, recruited by the nonagenarian philosopher Bertrand Russell, constituted themselves into a self-proclaimed ‘tribunal’ to try the United States of America for its conduct in Vietnam. After holding hearings in Sweden and in Denmark, they convicted the US of waging an illegal war of aggression against Vietnam, of war crimes and, most sensationally, of ‘genocide against the people of Vietnam’.

Then, nothing much happened. The verdicts were welcomed by those who were already convinced of America’s immorality in Indochina and mocked by everyone else, before being forgotten entirely. Even though the American public’s mood eventually soured on the war, the Russell Tribunal had little to do with it. Today, its main legacy lies in the numerous copycat tribunals it has inspired, staffed by cranks, convened in cavernous public buildings, rendering verdicts that, just like the Russell Tribunal’s condemnations of US policy in Vietnam, were never in doubt.

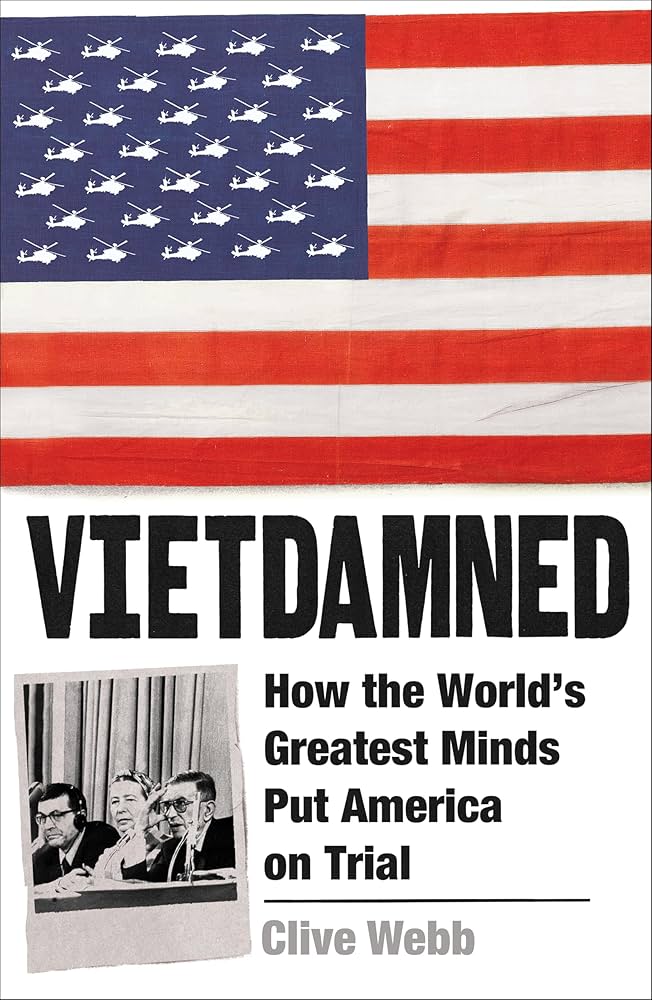

As Clive Webb candidly admits in Vietdamned: How the World’s Greatest Minds Put America on Trial, posterity has been unkind not only to the Tribunal, but to the force behind it. One of Lord Russell’s biographers described his involvement with the venture, as well as his anti-Vietnam War activism more broadly, as ‘a quite colossal vanity’, designed to prove to himself that he still mattered to the world even as his body was failing. In Vietdamned, Webb aims to rescue the Tribunal from the contemptuous footnotes of history, and Russell’s last decade from the embarrassment of his biographers.

He does not succeed in doing either, but not for lack of trying. Webb, who is in obvious sympathy with the aims of the Tribunal and an admirer of Russell, Victorian aristocrat-turned moral prophet of the nuclear age, puts forward his case for both with skill, backed up by impressive research. In fact, the book is as much a history of the Russell Tribunal as it is a mini-biography of Russell and of the French philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre, the latter of whom dominated the Tribunal’s proceedings (Simone de Beauvoir, billed as the third key protagonist, gets short shrift).

The Tribunal’s two sessions, by contrast, are treated with surprising brevity: the hearings were not very dramatic, and Webb’s narrative of the formal portion of the Tribunal is only rescued from descriptive boredom by stories of clashes between its members, some of whom achieved a level of personal disagreeableness that is impressive even by the standards of intellectuals with revolutionary pretensions. Vladimir Dedijer, the Tribunal’s chairman, seemed to have been particularly dislikeable; and one cannot help but sympathise with Tito’s decision to saddle the Americans with him by driving him into Western exile.