Immediately after the two territories of Hawai‘i and Alaska became states, the moon rose high on the horizon of U.S. ambitions. For President Kennedy, who proposed a landing, it was a “new frontier.”In fact, from the perspective of empire, it was a frontier like none before—large, uninhabited, rich in minerals, and newly accessible. This is exactly the sort of thing that would have set old-school empire-builders trembling with anticipation. “I would annex the planets if I could,” the British arch-imperialist Cecil Rhodes had once mused.

Annexing the moon, however, would only make sense if it had value and if it could sustain cities, bases, or mining operations. Could it?

It is tempting to assume that settling space was never more than a science fiction fantasy. But that’s a retrospective judgment. One has to appreciate the wrenching technological transformations that the leaders of the United States had already experienced in their lifetimes. Dwight Eisenhower was born into a world containing a countable number of cars, where light bulbs were still a novelty. Yet he lived to see television, computers, nuclear bombs, supersonic jets, and satellite communication. Though he initially treated space exploration as a punchline, by 1958 Eisenhower felt compelled to admit that “a great many of us here will live to see things that today look just like Buck Rogers in the funny papers. That, I am sure of.”

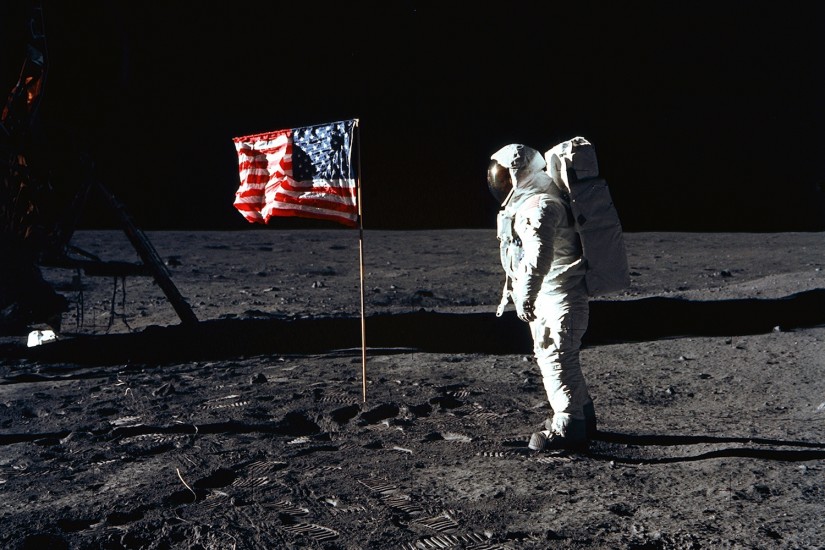

Eisenhower died in 1969, the year that—just like the spaceman hero Buck Rogers—astronauts touched down on the moon. Five years later, the New York Times ran a front-page story reporting that not only did respectable scientists believe space colonization to be possible, but that they had a plan for it. “We can colonize space,” announced a prominent Princeton physicist in Physics Today. He predicted that the first community would be in space before 2005. In 1975, NASA convened a study group on space settlement, which judged it to be both “technically feasible” and “desirable.” Carl Sagan, Buckminster Fuller, Lynn Margulis, Stewart Brand, and Jacques Cousteau all approved. Space colonies were “not a question of whether,” announced Jerry Brown, the governor of California, “only when and how.”