Candidates’ decisions to focus on punishment over treatment in 2024 was hardly new. In fact, that strategy has been a bedrock of U.S. politics throughout modern American history, speaking to Americans’ deep ambivalence toward psychotropic substances. Dating back to at least the late 19th century, a key question has shaped public drug debates: is addiction a disease best addressed through medical care, or is it a crime that deserves punishment? History shows us that the 2024 election represents just one more swing of the treatment/punishment pendulum that has stunted the country’s ability to manage drug use and addiction for more than a century.

This debate initially arose in the wake of the nation’s first federal drug laws. In 1914, Congress passed the Harrison Narcotics Tax Act, which for the first time made illegal the possession without a prescription of drugs like opium, heroin, morphine, and cocaine. As a result, thousands of American users who had been able to buy these substances legally and without a prescription were forced to turn to an illicit market. Treatment options for addicts were almost nonexistent, and many committed crimes so they could afford to keep up their habits. The number of Americans convicted of drug charges rose and federal prison populations increased to more than double their intended capacity. Shut out of medical care, locked up in prisons, and ostracized by the wider public, users and addicts seemed to have nowhere to turn.

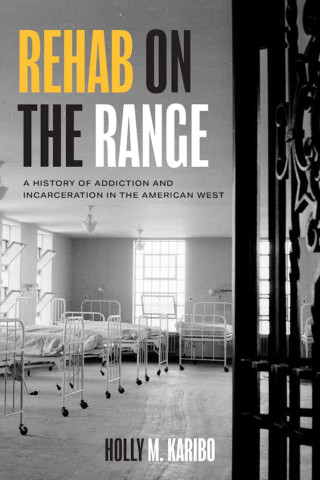

In response, a group of physicians, social scientists, and politicians came together to try to fix some of the problems created by the Harrison Act. In 1929, Congress passed the Narcotic Farms Act, which for the first time established federal funding for two institutions dedicated to addiction treatment. One would treat addicts living east of the Mississippi River (established at Lexington, Ky., in 1935) and the other would treat users living west of that line (established at Fort Worth, Texas, in 1938).

Framed as modern, progressive institutions that would transform addiction care, these “narcotic farms” serviced a combination of voluntary and prisoner patients, who physicians believed were all deserving of care. Social scientists studying criminal rehabilitation were thrilled that addict prisoners could be transferred out of overcrowded prisons. The media and the public lauded the narcotic farms as the first institutions in the world to take a humanitarian approach to the issue of addiction.