In the late 1930s, most Americans were opposed to intervening more in world affairs. They have gone down in history as “isolationists,” but that label is deeply misleading. To be sure, there were genuine isolationists who wanted to pull up the drawbridge over America’s two vast ocean moats, but they were decidedly in the minority. The majority wanted their nation to be active in the world, just strictly on its own terms.

They were best characterized as noninterventionists. Their standard-bearer was former president Herbert Hoover, as deeply internationalist as any of his fellow Americans. Yet Hoover was opposed to intervening in Europe or Asia. The Germans and Japanese were odious, he said repeatedly, but they posed no threat to the United States.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt strongly disagreed. The problem for Roosevelt, though, was that Hoover was indisputably correct on the most important part of the issue: Germany and Japan could not feasibly attack, let alone invade and occupy, the continental United States. If self-defense against physical attack was the objective of U.S. foreign policy, then Hoover’s argument would carry the day. And it did — public-opinion polling, then in its infancy, showed strong opposition to becoming embroiled in the political and strategic controversies convulsing Europe and Asia.

Roosevelt and his interventionist supporters knew they couldn’t win the debate if it was centered on traditional notions of self-defense. But to them, protecting U.S. shores wasn’t the issue; preventing another power with a hostile ideology from dominating much of the world was.

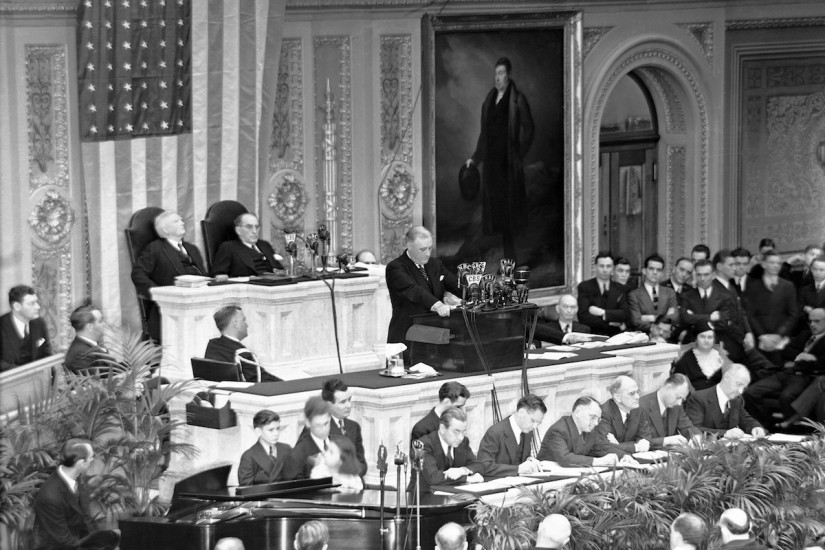

So Roosevelt changed the definition of self-defense and replaced it with an altogether new term that had seldom been used before: national security. Narrow definitions of self-defense, he argued, were obsolete in the modern world. “There comes a time in the affairs of men when they must prepare to defend not their homes alone,” he declared in his 1939 State of the Union address, “but the tenets of faith and humanity on which their churches, their governments, and their very civilization are founded.”

Between Japan’s invasion of China, in 1937, and its attack on Pearl Harbor, Roosevelt and his supporters hammered home this message. In this short time, Roosevelt invoked the phrase “national security” more than all other presidents before him, combined. He warned that America was in peril even if it was safe from a physical attack, and that a failure to act now would bring incalculable harm later.