Rumors that the Trump administration was more interested in the moon than Mars began circulating days after the inauguration. Leaked memos published in February revealed the president’s advisers wanted NASA to send astronauts there by 2020, one part in a bigger plan to focus on activities near Earth rather than missions deeper in the solar system. Vice President Mike Pence spoke vaguely of a return to the moon in a speech in July. In September, the administration nominated a NASA chief who extolled the construction of lunar outposts. All signs pointed to a significant shift in the country’s Mars-focused space agenda of the last seven years.

This week, the Trump administration made it official.

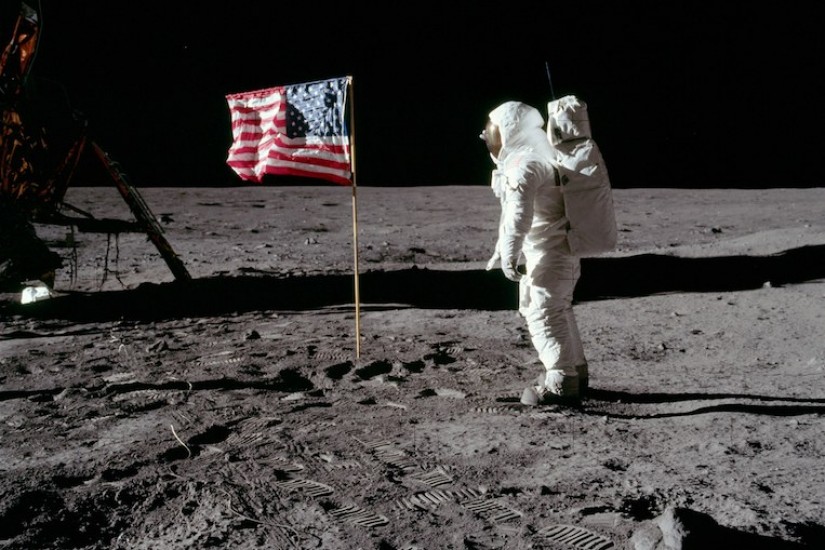

“We will return NASA astronauts to the moon—not only to leave behind footprints and flags, but to build the foundation we need to send Americans to Mars and beyond,” Pence said Thursday at the inaugural meeting of the National Space Council, an advisory body his administration recently revived.

The vice president’s comments marked a pivot from Barack Obama’s directive for a “Journey to Mars,” established in 2010, and harkens to the aspirations set forth by the George W. Bush administration. The Obama administration had maintained that some kind of human activity in cislunar space—the region between the Earth and the moon—was necessary to test technology for a mission to Mars, but the efforts would amount to a pit stop, not a destination.

While Pence did not provide details on what kind of “foundation” Americans would build on the moon, the new direction was clear: Americans should be spending more time in their cosmic backyard before flying off into the solar system.

“It’s a 180-degree shift from no moon to moon first,” said John Logsdon, a space-policy expert and former director of the Space-Policy Institute at George Washington University.