The president was frustrated. He was at odds with Congress. The regular workings of government didn’t let him do what he desperately wanted to do. So he went on national television to explain why a public policy impasse amounted to a national emergency allowing him to take extraordinary action.

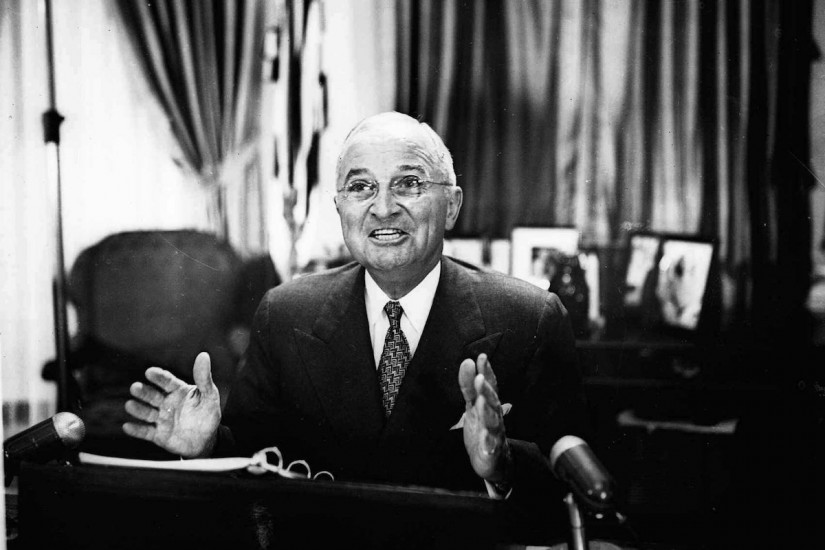

“My fellow Americans, tonight our country faces a grave danger,” President Harry S. Truman said from the White House on the night of April 8, 1952. “These are not normal times. These are times of crisis.”

Truman went on to explain why he had just directed his secretary of commerce to seize control of the country’s steel mills. An ongoing dispute between the companies and their workers threatened to deny U.S. troops the weapons and tanks they needed to fight in the Korean conflict.

“I would not be faithful to my responsibilities as president if I did not use every effort to keep this from happening,” he argued.

Truman’s actions 67 years ago sparked a fiery constitutional dispute that rocketed to the Supreme Court. And now, as President Trump considers claiming similar emergency powers to build his long-promised border wall despite lawmakers’ refusal to fund it, scholars are looking back at Truman’s gambit and the legal precedent it created. Suddenly, Youngstown Sheet & Tube Co. v. Sawyer, a great test of presidential power, is in vogue again.

“Youngstown is the right place to look,” constitutional scholar Jeffrey Rosen said. “But a lot has happened since then.”

Like Truman, Trump used a White House address to make the case that the United States is facing a security crisis at its southern border. Then he followed up with a trip to Texas Thursday as the administration began looking for unused money in the Army Corps of Engineers budget for the $5.7 billion the president says is needed for the wall.

A Trump declaration of a national emergency could end a partial government shutdown now in its third week, but will likely lead to congressional and court challenges.