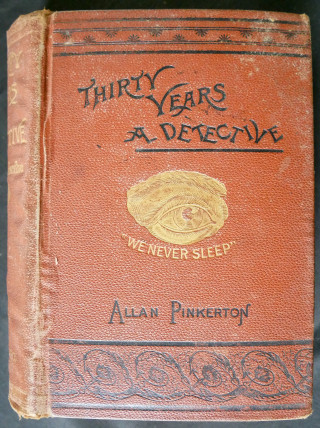

Thirty Years a Detective doesn’t mention Pinkerton’s Civil War work, which had ups and downs. He cleverly foiled an assassination plot on Lincoln, for instance, but he also supplied dubious intel that likely lengthened the war. One of his undercover detectives was exposed by two others, and hanged by the Confederates. When Lincoln canned McClellan, Pinkerton resigned and returned to his Chicago business, taking the logo of a disembodied eye above the slogan, “We Never Sleep”. It’s said that the agency he subsequently built served as the model for the FBI.

There’s no doubt that Pinkerton shaped the history of American vice, though the motley anecdotes collected in Thirty Years a Detective are mainly lighthearted curiosities, hijinks to entertain a group of chums at the bar. Pinkerton’s focus is the “how” of a crime, not the “why”. The book is a compendium of pragmatic details that only a detective would know: the delicate choreography of pickpocketing, the engineering of specialized burglars’ tools, the code words, the backroom money split. It’s a useful read for, say, a historical novelist, so long as she doesn’t expect insights into criminal psychology.

The anecdotes are grouped according to the type of crime, with each given its own chapter. There are sections on forgery, counterfeiting, blackmail, and a surprising variety of thieving techniques. Thieves who worked steamboats had different methods than those who worked train cars, hotels, or theaters. Bank robbers are a class above, and pickpockets a class below. Some thieves specialize in weddings, and others in funerals. Faked pregnancies are found in the “Confidence and Blackmail” chapter. There is no chapter on murder.

Arcane facts galore. When sleeping in a hotel, nineteenth-century Chicagoans kept their cash under their pillow, such that stealing it required preternatural silence. Wearing wool was quieter than wearing cotton.

The best pickpockets remove a woman’s wallet, sweep the contents, and then return it, so that when she pats her purse, nothing seems amiss. The industry term for this is “weeding the leather”. Pickpockets who target women are called “moll-buzzers”; pickpockets who target men are “bloke-buzzers”.

“American housebreakers”, Pinkerton reports, are “far more expert and daring” than their British counterparts. The Brits tend to work slowly, in careful, methodical groups, whereas the Americans are lone rangers, more impervious to fear.